Benito Mussolini was born in Predappio, northern Italy, in 1883. Growing up, he was strongly influenced by the socialist views of his blacksmith father. Though he was a bully at school and often badly behaved, Mussolini nevertheless qualified as a teacher in 1901. He moved to Switzerland in 1902, in order to avoid military service. There he became an active socialist and trade unionist, giving speeches and working for a socialist newspaper. In 1904 he returned to Italy to complete his military service. By 1911 he had become a leading socialist and editor of the Italian Socialist Party’s newspaper.

Young Mussolini.

When the First World War broke out in July 1914, Italy remained neutral. Mussolini at first opposed the war, along with his party, but as nationalism surged throughout Europe, he argued that Italy should join the Allies, since the war would trigger anti-imperialist revolutions and liberate those Italians still under Austro-Hungarian rule. The Socialists expelled him in October 1914 for his pro-war stance, but in November Mussolini, now funded by an armaments firm, started his own pro-war newspaper, called “The People of Italy”. In a speech given in December 1914, Mussolini maintained:

“The nation has not disappeared. We used to believe that the concept was totally without substance. Instead we see the nation arise as a palpitating reality before us! Class cannot destroy the nation. Class reveals itself as a collection of interests—but the nation is a history of sentiments, traditions, language, culture, and race. Class can become an integral part of the nation, but the one cannot eclipse the other.”

Though still a socialist, Mussolini was critical of dry theoretical Marxism, believing that the masses needed to be guided by a revolutionary elite and inspired by strong emotions and violent myths. Accordingly he founded the Fasci d’Azione Rivoluzionaria (Revolutionary Action Group) in December. A “fascio” (plural “fasci”), meaning literally “bundle”, was a loose political grouping. Many other pro-war “fasci” now sprang up.

Italy eventually joined the Allies in May 1915, tempted by promises of territorial gains. Mussolini entered military service in August 1915 but was invalided out with mortar injuries in February 1917. Italy initially suffered many military setbacks, but by early November 1918 it had occupied Austria-Hungary’s entire coastline, including Dalmatia. By the end of the war, however, Italy had lost 600,000 men and inflation was rampant. Italy gained the South Tyrol and part of Istria from Austria-Hungary, but the Allies gave Dalmatia, initially promised to Italy, to the new state of Yugoslavia, and furious Italian nationalists now denounced the “mutilated peace”.

In March 1919 Mussolini founded the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Combat Group) in Milan, with around 200 members of varying political views, but all of them extreme nationalists. Some were demobilised assault troops from the war. These battle-hardened young thugs continued to wear the black-shirted uniform and became known as “Blackshirts”, or alternatively “squadristi”, members of Mussolini’s action squads. However, Mussolini’s group gained only 0.5% of the vote in the November 1919 general election. The Socialists came first, followed by the Catholic People’s Party. Their mutual distrust prevented them forming a majority government, so the corrupt and oligarchic liberal elite continued to provide a weak minority government.

Fascist Blackshirts from a Fascio di Combattimento, 1920

In September 1919, with the help of 300 supporters, Gabriele D’Annunzio, a nationalist poet and war hero, occupied the city of Fiume (now Rijeka, in Croatia), which he believed to be Italian, proclaiming himself Duce of the Regency of Carnaro. He lamented that Italians, despite the unification of 1870, still did not think of themselves as a country. “We have made Italy, but we have not made Italians“. In Fiume he developed rituals, parades, ceremonies, uniforms and a style of salute that would eventually be copied by Mussolini. He also harangued audiences from a balcony and devised a constitution based on corporatism. On 12 November 1920 the League of Nations approved the Treaty of Rapallo, which overrode D’Annunzio and made Fiume a Free State. D’Annunzio refused to recognise this, then declared war on Italy. On 24 December 1920, the Italian government bombarded the port and forced D’Annunzio and his supporters to surrender the city. Mussolini had watched the affair with interest, while keeping his distance, though it proved to be a great influence on his political style. After D’Annunzio sank into oblivion, attention switched to Mussolini as Italy’s premier nationalist.

Meanwhile, through 1919 and 1920, the economic crisis in Italy caused soaring industrial and agricultural unrest. Strikes proliferated and, in August and September 1920, workers occupied factories and declared workers’ councils, while landless peasants seized plots of private land. Many feared there would be a Soviet-style revolution, but a weak government backed down and made concessions to peasants and workers. The unrest died down, but socialists still ran many municipalities, and frightened and vindictive landowners and industrialists now launched their fight-back. Increasingly they paid Mussolini’s squadristi to attack socialists and trade unionists and burn down their headquarters around the country. The anti-fascist Left was no match for the Blackshirts, who were better organised, better armed and far more brutal. Meanwhile, the police and military often cheerfully stood back or even supplied the Fascists with weapons, despite the government’s attempts to forbid this.

From “Mussolini the revolutionary”, by de Felice:

Between the end of 1920 and the first months of 1921, the Fasci completely changed physiognomy, character, social structure, key centres, ideology and even members. Of their leaders only Mussolini and a very few others completely followed this change in all its phases. Many original members fell by the wayside, and a number even passed over to the opposite side, but the majority almost inadvertently found themselves at a certain point different from what they had been in the beginning, supplanted in the leadership of the movement by new elements, of diverse origin and development, tied to quite different realities.

Fascism, finding the political space on the left already occupied, had now found a vacant space on the right. Fascist membership surged to almost 190,000 by May 1921, and the Fascists won 35 seats in that month’s general election. Mussolini, now a deputy, renamed his movement the National Fascist Party in November 1921. He shunned the three weak coalition governments that followed, denouncing socialism and liberalism alike. Going into 1922, in northern Italy the Fascists took over yet more regional councils by force, but still the state declined to intervene. Mussolini claimed that Fascist violence was a defence against the “red menace”, and he was eagerly believed by many. In October 1922, the impatient regional Fascist bosses urged Mussolini to launch a Fascist coup, but he would agree only to a Fascist “March on Rome”, to pressurise the government.

On October 27, Fascist squads took over strategic points across northern Italy and the march began. The military and police pledged their loyalty to the King, confident they could easily defeat the roughly 30,000 lightly armed Fascists. Next day the Italian premier advised the King to declare martial law. The King hesitated and so the premier resigned in protest. A nervous Mussolini had remained in Milan, but on the evening of October 29, the King asked him by telephone to join a new government. Emboldened, Mussolini insisted on becoming Prime Minister. The King agreed. He wanted an end to weak government and to avoid a potential civil war by co-opting and taming the Fascists, who already had much support within the establishment. On October 30, Mussolini travelled to Rome by train to become premier. His marching Fascists arrived the next day, and Mussolini briefly joined them to pose for photographs. He now fronted a coalition government, but the establishment had unwittingly invited a cuckoo into the nest.

The March on Rome: Mussolini and his Fascists, October 1922.

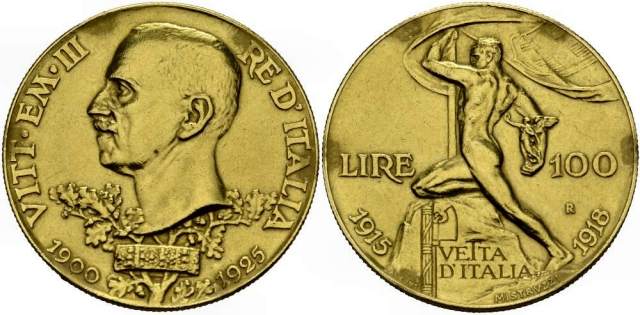

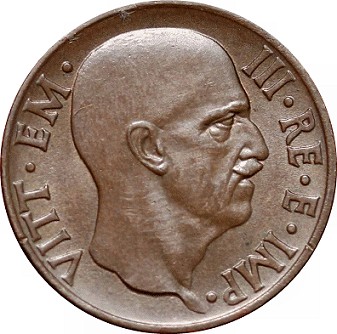

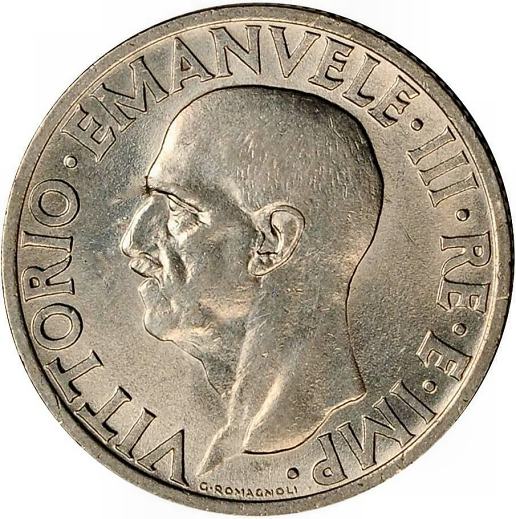

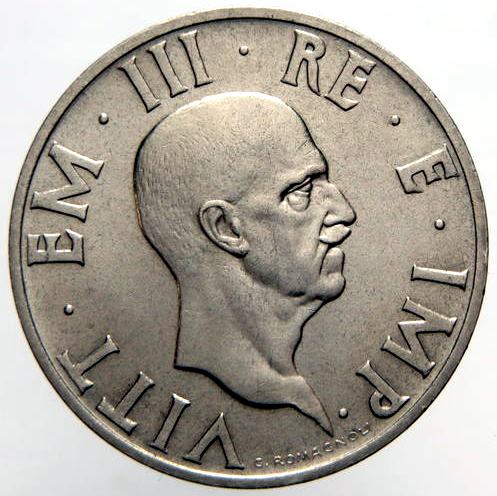

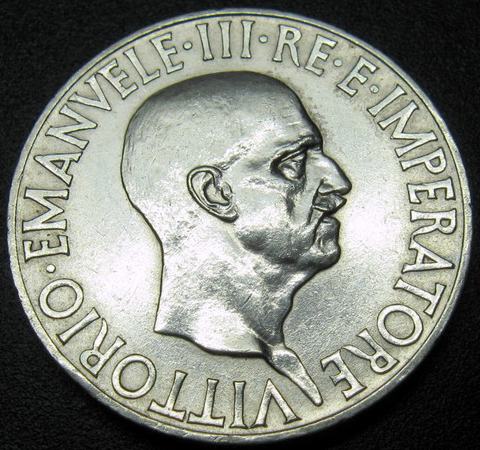

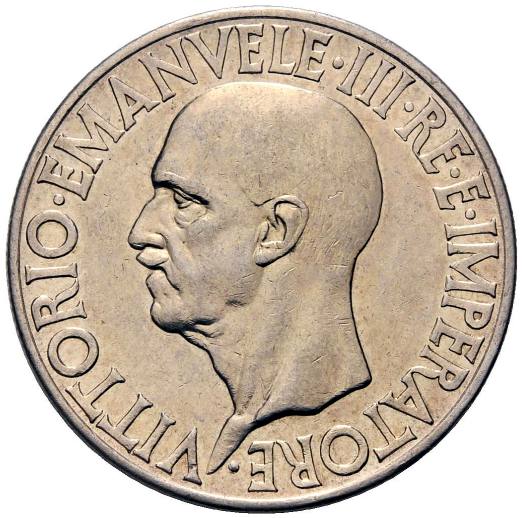

Gold 20 lire and 100 lire coins were issued in 1923 to commemorate the anniversary of the March on Rome. The coins show King Vittorio Emanuele III on the obverse and the fasces on the reverse. The Fascists had adopted the Roman fasces as their party symbol. The fasces, a bound bundle of rods enclosing an axe, was an ancient Roman symbol of state authority, which the Fascists had adopted as their party emblem. The Fascists had blasted out an ideological space for themselves by claiming to be heirs to the ancient Roman spirit, with which they would forge a modern Roman empire. The bound rods symbolised strength through unity, reflecting the collectivist ethos of the Fascist mass movement. The fasces represented discipline and potential punishment, again reflected in the Fascist slogan of “Order, discipline, hierarchy”. The Fascists despised what they saw as the sordid compromises of democracy and its insipid egalitarianism, lauding instead strong leadership and heroic acts and maintaining they had seized power through their March on Rome. In fact, the marching Fascists had arrived in Rome only after a power-sharing deal was made. In Munich, an admiring Hitler believed the myth and attempted his own coup in October 1923, but he learned a harsh lesson when it was swiftly put down.

Italy, gold 20 lire, 1923.

Italy, 100 lire (gold), 1923.

A nickel 2 lire non-commemorative circulation coin, with a similar reverse design to the 20 lire coin, was also issued from 1923 to 1927. The 2 lire reverse was designed by Publio Morbiducci but engraved by Attilio Motti. Morbiducci later produced some superb patterns in the competition for the Irish Free State’s first coinage. The 20 lire reverse was designed and engraved by Motti. Curiously, he replaced the usual lion’s head, above the axe blade, with a ram’s head.

Italy, 2 lire, 1923.

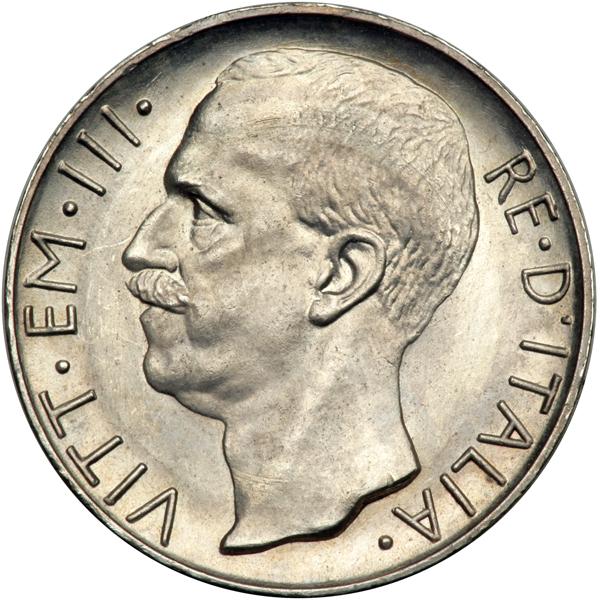

Over the next two decades, the fasces would become as ubiquitous in Italy as the hammer and sickle in the Soviet Union. Fascism, the bastard child of socialism, came to be seen as the mirror opposite of communism, and both were collectivist mass movements that aspired to a one-party totalitarian state. However, the royal portrait on these coins emphasises one major difference: whereas communists came to power by force and smashed the existing system, the Fascists were helped into power by the existing elites. Fascist Italy was in fact a diarchy, in which the King remained head of state, while Mussolini was head of government. Though Mussolini styled himself “Il Duce” (“The Leader”), his portrait never appeared on the coinage; by tradition, that privilege was reserved for the head of state, namely the King. But the monarchy and Fascism were now locked in an embrace that would end in their mutual destruction.

The fasces had appeared on many coins worldwide before the Fascist regime adopted it, most notably on the US dime, from 1916 to 1945.

US Mercury dime with fasces, 1936.

Mussolini initially ruled by emergency decree for one year, introducing business-friendly laws, but now in July 1923 he proposed an election law that would give two-thirds of parliamentary seats to the party with the most votes, provided it gained at least 25% of the votes. Many deputies abstained but, with armed Fascist guards at the doors, the remainder was intimidated into voting for the law. The general election was held in April 1924, amid much intimidation, and the Fascist Party duly gained 65% of the vote, so the new law made little difference. When parliament convened on May 30, socialist deputy Matteotti denounced the Fascists’ violence and electoral fraud. On June 10 he disappeared, and his body was found on August 16. He had been murdered by Fascist thugs, who were duly imprisoned. Mussolini denied involvement but remained paralysed with indecision as the scandal dragged on. On December 31, thirty leading Fascists told him to declare a dictatorship or else they would depose him. On January 3 1925, a combative Mussolini told parliament that he accepted responsibility for Fascist errors. However, he would not resign but would continue to govern Italy – “by force, if necessary.” In a still polarised country, he retained the confidence of the King and the establishment. He now purged his violent squadristi but also took control of the Press and banned trade unions (apart from Fascist ones) and strikes. After a failed assassination attempt against him in 1926, he banned all opposition parties, and in 1927 he created a state secret police force. For Mussolini, the state was paramount: “Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.” In 1928 he replaced parliament with the Chamber of Fasci and Corporations. His rule was now complete, and he was answerable only to the king.

After the commencement of Mussolini’s dictatorship, Italy predictably issued more coins with Fascist-inspired designs. A gold 100 lire coin of 1925 jointly commemorated the King’s silver jubilee and the tenth anniversary of Italy’s entry into the World War. The reverse includes the fasces and shows a nude male holding a statue of the goddess of Victory, while kneeling on “The Peak of Italy” (Vetta d’Italia) and planting an Italian flag on it. This mountain stands in former Austrian territory that was ceded to post-war Italy. Until now, nudes on Italian coins had been female, but Fascism was a fundamentally masculine creed. The muscle-bound male projects the youth, virility and heroism to which Fascists aspired. That this distinctly propagandistic piece commemorates World War I is particularly apt, since Fascism derived all its values from that war: murderous nationalism, state-directed violence, and the militaristic values of discipline, hierarchy and camaraderie.

Italy, 100 lire (gold), 1925.

A new silver 10 lire was issued in 1926. Its reverse shows an allegorical female driving a chariot. Only the fasces held by the woman identifies this as a Fascist issue.

Italy, 10 lire, 1926.

A new silver circulation 5 lire was issued in 1926, through to 1935. The reverse depicted an eagle, perching on the fasces. Such fierce eagles were portrayed on the military standards of ancient Rome, whose martial qualities Fascism aspired to emulate. Fascist propaganda made constant allusions to ancient Rome.

Italy, 5 lire, 1926.

Unadopted trial design of the 5 lire.

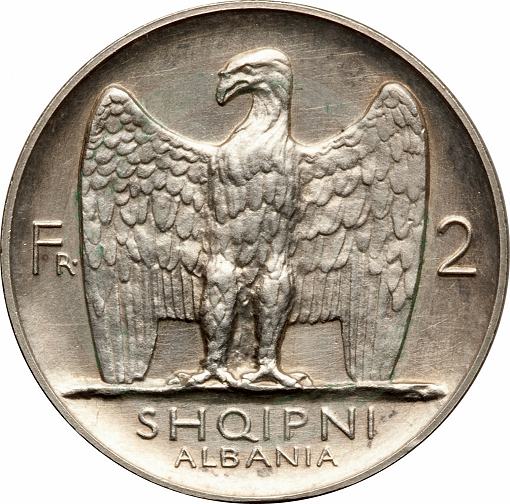

Compare the 5 lire to the Albanian 2 franga ari of 1926, also a product of the Rome Mint.

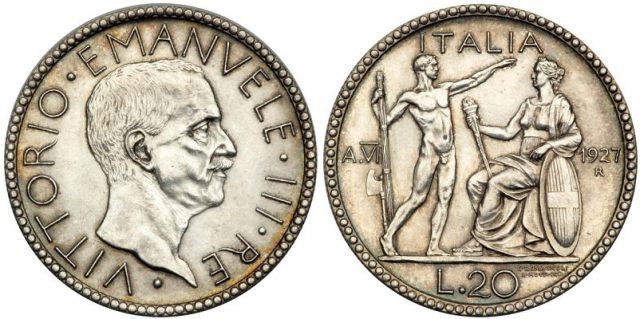

Yet like the Jacobins of the French Revolution, the Fascists also claimed to have inaugurated a new era, which required its own calendar: Year 1 of the Fascist Era accordingly began with the march on Rome in 1922. A new silver 20 lire, issued in 1927, was the first coin to give the year in both the Christian era and the so called Fascist era. However, the commonly issued version of this coin shows the letters “A.VI” next to the fasces, an abbreviation of “Anno VI”. Only 100 pieces were minted with the correct Fascist Year 5, “A.V”. A 1928 version of the coin was issued with the Fascist year correctly shown as “A.VI”. The Roman numerals overtly allude to the Fascists’ identification with ancient Rome. The reverse design shows a standing nude male holding the fasces before a seated Italia, perhaps symbolising Fascism protecting Mother Italy.

Italy, 20 lire, 1927.

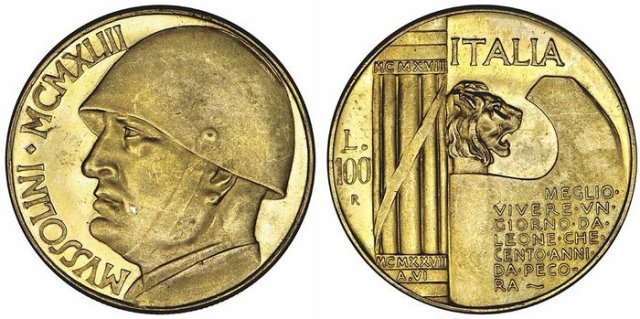

Also in 1928, a blatantly triumphalist 20 lire silver coin was issued to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the World War. The reverse design showed a fasces, on whose axe blade was written the boastful motto: “Better to live one day as a lion than a hundred years as a sheep”. The obverse design continued the war-like theme by portraying the King in a military helmet.

Italy, 20 lire, 1928.

By 1928, Mussolini, aided by his skilful propaganda, was admired by many in the West as a moderate and effective dictator, who provided strong government after Italy’s years of strife. In 1870 the Kingdom of Italy had annexed the last of the Papal States, earning the enmity of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1929 Mussolini negotiated the Lateran Pacts with the Holy See, whereby the Vatican City was given its own small sovereign state and financial compensation for its territorial losses. Mussolini, the former socialist, atheist and anti-clerical republican, had now made his peace with both the Pope and the King – to the disgust of many early Fascists, who had long since left the Party. This acted as a restraint on his regime, which, though repressive, was far less brutal than some of its contemporaries.

Mussolini and the King.

Fascism claimed to transcend class conflict, and this sense of idealism appealed to many Italians. Its emphasis on action particularly appealed to young people and students. Its reverence of the state appealed to people who worked in the public sector, but generally not to front line workers in private industries, such as miners and factory workers. In practice, the banning of strikes and the state’s need to favour productivity over consumerism meant that the Fascist regime was right-wing. It took care, however, to give some sops to workers, and its Dopolavoro (“After work” organisation) provided the public with various free and subsidised leisure activities, so that Fascism seemed to penetrate much of public and private life. But by now, most Fascist party members were mere opportunists, since membership could help advance their career.

Fascist Italy issued a gold 50 lire collector coin in 1931, whose legend, as was now standard practice, references both the Christian and Fascist era years: “1931-IX”. The reverse design shows a Roman lictor with fasces. A lictor was a Roman civil servant who acted as a bodyguard to magistrates.

Italy, 50 lire (gold), 1931.

A companion gold 100 lire coin was also issued. Its reverse design features the fasces superimposed on the prow of a galley, on which an allegorical Italia is standing. The legend “IX.E.F” refers to Year 9 of the Fascist era (“Era Fascista”). The 50 and 100 lire coins were also issued in 1932 and 1933, bearing the appropriate dates.

Italy, 100 lire (gold), 1931.

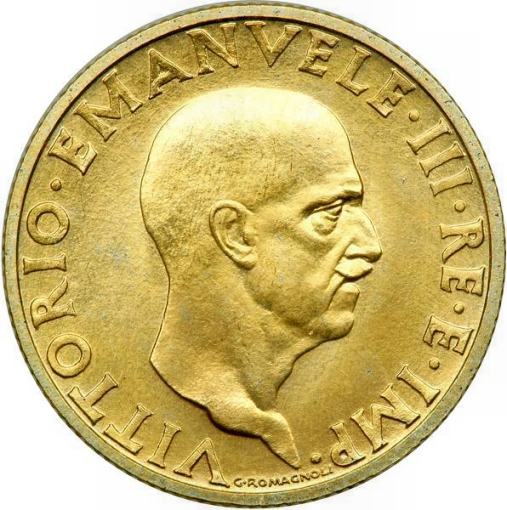

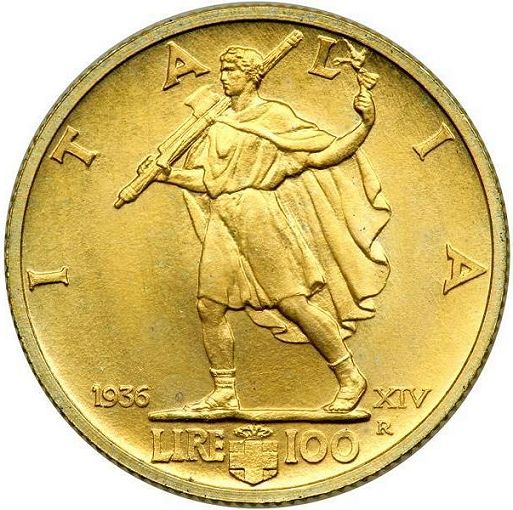

After the Great Depression hit, extremist politics became vogue and Fascism was much imitated across Europe by new extremist parties. Hitler came to power in 1933 as an avowed admirer of Mussolini, but the Duce, who had a Jewish mistress at that time, was unimpressed by Hitler’s bizarre racist theories. When Austrian Nazis murdered Austrian chancellor Dollfuss in a failed coup attempt in July 1934, Mussolini rushed troops to the Austrian border to warn Hitler off. Yet Mussolini harboured his own ambitions and now that he had consolidated his rule, he was looking for opportunities for glory. At home, he was increasingly stung by criticisms that he was presiding over a stagnant regime that lacked direction. In 1935 Mussolini decided to invade Ethiopia, Africa’s only remaining independent state, as a response to its border skirmishes with Italian Somaliland. After its conquest in 1936, Mussolini merged it, with Italian Eritrea and Somaliland, into Italian East Africa, and King Vittorio Emanuele was made Emperor of Ethiopia. Mussolini’s popularity in Italy was now at its height. In that same year, a new design series was released to celebrate the newly extended Italian Empire. The obverse legends now incorporated a reference to the King’s new status of Emperor. The Italian coinage was now become fully Fascist. Four different designs of an eagle perched on the fasces appeared on the 5 and 50 centesimi coins and on the 1 lira and 2 lire coins. These superb eagle designs echoed a similar 5 lire design of 1926. All the reverse designs showed the fasces and the crowned shield of the House of Savoy.

Italy, 5 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 5 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 20 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 50 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 1 lira, 1936.

Obverse of the 1 lira coin.

Italy, 2 lire, 1936.

Obverse of the 2 lire coin.

The silver 5 lire coin depicts a mother with four children, representing “fertility”. Mussolini had instigated his pro-natalist “Battle for Births” policy in 1927, aiming to increase Italy’s population from 40 to 60 million by exempting families with ten or more children from income tax. He believed that a “great power” such as Italy required a large population, with which to wage war and conquer new territory. For that, he needed Italy’s mothers to provide him with lots of Fascist babies, who he hoped would grow up to join Italy’s conquering armies. The propagandistic “fertility” design was therefore an invocation to Italy’s women to remember their duty.

Obverse of the 5 lire coin, 1936.

Italy, 5 lire, 1936.

Mussolini inspects the Fascist baby production line.

The designs of the circulation silver 10 lire coin and the gold 50 lire collector coin echoed the designs of the 50 and 100 lire gold set of 1931, while the design of the silver 20 lire (a woman driving a quadriga) was reminiscent of Italian designs of the First World War. The gold 50 lire coin, however, carried a design that cleverly incorporated the fasces and the royal shield as parts of an ancient Roman standard, topped by the traditional eagle. The obverse designs portrayed the King as usual, but the legends now celebrated his new imperial status (“IMP”, “IMPERATOR”).

Obverse of the 10 lire coin.

Italy, 10 lire, 1936.

Obverse of the 20 lire coin.

Italy, 20 lire, 1936.

Obverse of the gold 50 lire coin.

Italy, 50 lire (gold), 1936.

Obverse of the gold 100 lire coin.

Italy, 100 lire, 1936.

In November 1935 the League of Nations had censured Mussolini for his invasion of independent Ethiopia. In his isolation Mussolini now cultivated Nazi Germany as an ally, and when the Spanish civil war broke out in 1936, the two dictators provided military aid to General Franco and his nationalists. The Fascist slogan, “Believe, obey, fight!” reflected the Duce’s old-fashioned view that war kept a nation fit. Mussolini did not object when Hitler annexed Austria in 1938 and then dismembered Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939. Mussolini nevertheless regarded Hitler with fear and envy, and in 1938 he cynically introduced his own anti-Jewish laws to appease the Führer. Fortunately, most Italians ignored them. Many now felt Mussolini was “licking Hitler’s boots”; nor did they welcome war in Europe, and Mussolini’s popularity plummeted. But because he believed Italy’s destiny was to dominate the Mediterranean, and to compete with Hitler, the Duce ordered the invasion and conquest of Albania, which was completed in five days, from April 7 to April 12, 1939. Vittorio Emanuele now became King of the Albanians, and, between 1939 and 1941, coins were minted for Albania that showed his portrait on the obverse, while the reverse of the higher denominations depicted the Albanian eagle between two fasces, with the year shown in its Christian and Fascist era versions. On the 0.20, 0.50, 1 and 2 lek coins, the King wears a military helmet, which must have been deeply humiliating to the Albanians who used them.

After Germany invaded France in May 1940, Mussolini, expecting a swift German victory, cynically declared war on France and Britain on 10 June 1940. His troops invaded France ten days later. After its defeat, France signed an armistice with Germany on June 22. A Franco-Italian armistice was signed on June 24. Italy then annexed part of Menton, in South East France, and also established a small occupation zone that included Nice and Grenoble.

Italy, 5 lire, 1940 – trial.

In October 1940 Mussolini invaded Greece, but by November the brave Greeks had the Italians on the back foot. Hitler intervened with a blitzkrieg occupation of Greece and also Yugoslavia, but to do so he had to postpone his planned invasion of Russia. Mussolini gained Dalmatia, most of Slovenia, and established a protectorate over Montenegro, but Italy did not issue any special coinage for these new conquests and annexations.

Germany: “Two peoples and one struggle”.

Libyan stamps, 1941: “Two peoples, one war”.

Italy, 1941: “Two peoples, one war”.

Originally Mussolini had reckoned on a short European war, not a protracted world war. Financially, his military exploits to date had proved extremely costly, since Italian industrial output could not match that of Britain or Germany, meaning that Italy’s military was grossly under-equipped. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, both Mussolini and Hitler declared war on the USA. One year later, the USA dropped the use of the Bellamy salute, which had originated in 1892 as part of the Pledge of Allegiance, because it resembled the Fascist and Nazi salutes.

Disaster beckoned as the British gradually trounced Italy’s forces in North Africa, and by 1943 industrial unrest swept across Northern Italy itself. Italians had lost faith in Mussolini and no longer wanted to fight Germany’s war. Anglo-American forces took Sicily on July 9 1943, and at a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 24 July 1943, dissident Fascists voted for the King to reassume his governmental powers. An apathetic Mussolini ignored the vote, but when he visited the King next day, the King dismissed him as prime minister and placed him under military arrest.

The military flag of the Italian Social Republic featured a Roman eagle clutching the fasces.

On September 8, as the Allies were liberating southern Italy, the Germans occupied northern and central Italy, rescuing a reluctant Mussolini and installing him as dictator of the short-lived Italian Social Republic. The rump regime issued a few stamps and banknotes but no coins.

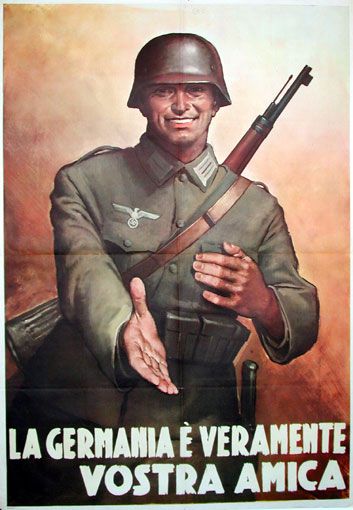

Unsubtle propaganda in the Italian Social Republic: “Germany is truly your friend”.

In reality, Mussolini was now the mere figurehead of a German puppet state, where the brutal German military administration, aided by die-hard Fascist collaborators, made all the important decisions. Its nominal capital was still Rome, but its de facto capital was the small town of Salò. According to Stanley Payne, a historian of fascism: “The experience of the Salò regime discredited Mussolini more than the twenty years of Fascist government which preceded it.”

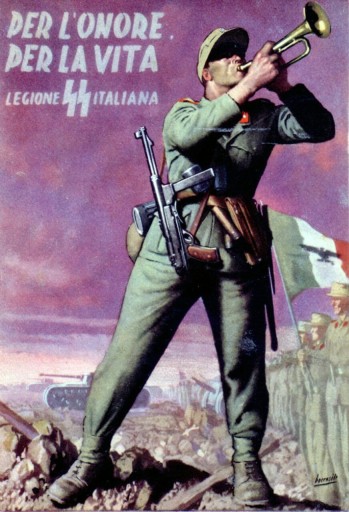

Around 15000 Italians fought in the Italian Waffen-SS Legion. The Nazis recruited many foreign nationals into the Waffen-SS.

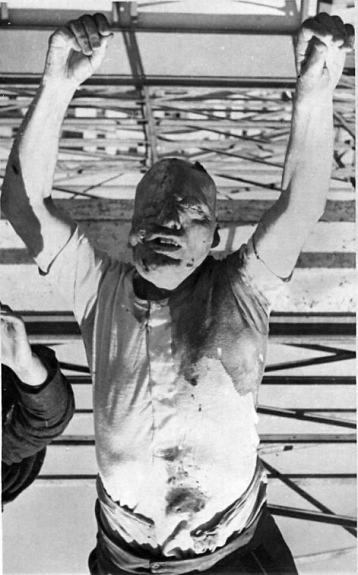

Meanwhile the King fled to southern Italy with his military government, where he arranged an armistice with the Allies. On October 13 1943 his government declared war on Germany, and the two Italian regimes descended into the chaos of civil war: Allies and partisans versus Nazis and Fascists. In April 1944, the King transferred most of his royal powers to his son, Umberto. On 27 April 1945, partisans captured Mussolini and his mistress en route to Switzerland, as they tried to escape. Both were executed by shooting the next day. Their bodies were taken to Milan, where they were hung upside down outside a petrol station and mutilated by an angry mob. Meanwhile, in Berlin, Hitler blamed his own downfall on his “fatal friendship” with Mussolini, before committing suicide on April 30. Though Mussolini’s dictatorship had been mild compared to Hitler’s, his regime’s naked aggression abroad meant that it reaped a rich harvest of retribution, and he deserved his ignominious fate.

Mussolini’s body hangs upside down in Milan.

From Wikipedia:

Initially, Mussolini was buried in an unmarked grave but, in 1946, his body was dug up and stolen by fascist supporters. Four months later it was recovered by the authorities who then kept it hidden for the next eleven years. Eventually, in 1957, his remains were allowed to be interred in the Mussolini family crypt in his home town of Predappio. His tomb has become a place of pilgrimage for neo-fascists, and the anniversary of his death is marked by neo-fascist rallies.

Mussolini brought death and destruction to his country. It is quite remarkable that anybody should want to honour such a failure.

The King abdicated in May 1946 and was briefly succeeded by his son, Umberto III. In a referendum the following month, 52% of the electorate voted to abolish the monarchy, which had been fatally tainted by its close association with Fascism. The ex-King retired to Egypt, where he died in 1947. Umberto moved to Portugal and died in 1983.

In 1999 and 2000, Italy issued a series of collector coins entitled “Goodbye to the lira”. It reproduced lira designs from the first half of the twentieth century. Astonishingly, one of them was the distinctly Fascist lira design of 1936.

Italy, 1 lire, 2000.

Just imagine if the Germans had reproduced a design depicting the Nazi swastika.

After the war, various fantasies portraying Mussolini were produced in Italy in the 1970s, by and for neo-fascists. Their reverse designs are clearly based on those of actual Italian coins of the 1920s. Because of this, some collectors believe that these fantasies must be trials, patterns or even fantasies produced during the Italian Social Republic, or during the prior Fascist regime of the Kingdom of Italy. This is emphatically not the case. No such patterns or trials were produced by either of the Fascist regimes, nor were any such unofficial fantasies produced during those periods.

Mussolini fantasy of the 1970s.

Mussolini fantasy of the 1970s.

After World War 2, a fantasy set of supposedly unissued stamps for Alpenvorland-Adria appeared on the market. It was alleged that they were produced in the final days of the war. In 1943 the German military had occupied the South Tyrol, which was part of the territory of the Italian Social Republic, with the intent of re-merging it into Austria. Austria was of course part of Germany at that time, having been annexed in 1938. See: Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills. The Italy had itself originally annexed the South Tyrol, which still was home to many ethnic German-speaking Austrians, as a result of the post-First World War territorial treaties. Though these alleged stamps were produced to a high standard and look similar to, though different from, the war-time set for “Provinz Laibach” (German-occupied Slovenia), it is clear, for various reasons (including the type of paper used), that they could not have been produced before the 1960s. They are therefore, however fascinating, mere fantasies (or “cinderella stamps”).