Here are a few 20th century coin designs by the Royal Mint whose designers I would like to know.

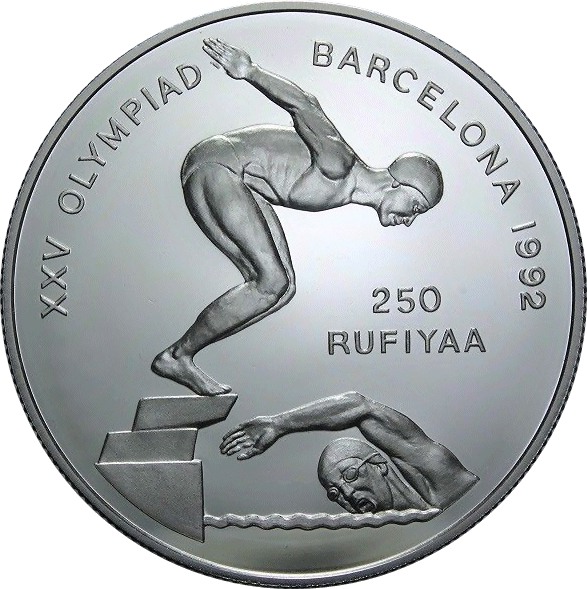

Maldives

Maldives, 250 rufiyaa, 1992. Olympics.

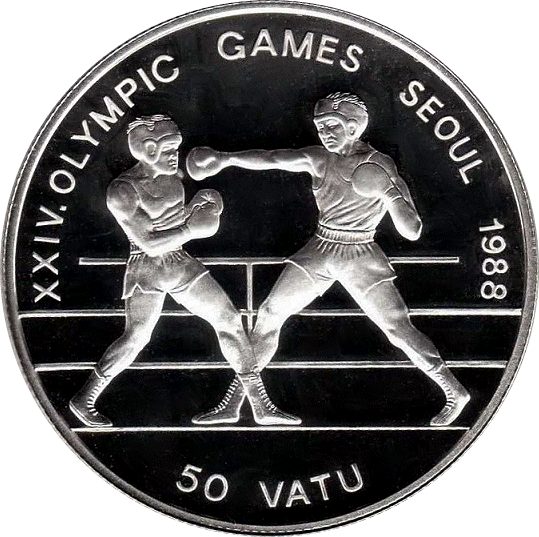

Vanuatu

Vanuatu, 50 vatu, 1988. Olympic boxers.

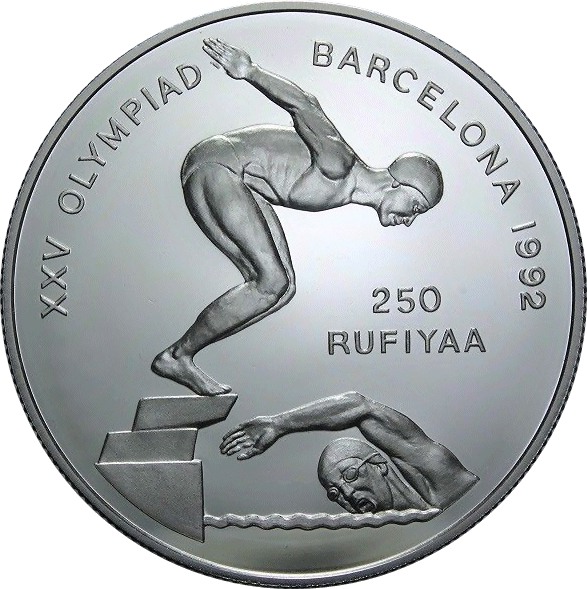

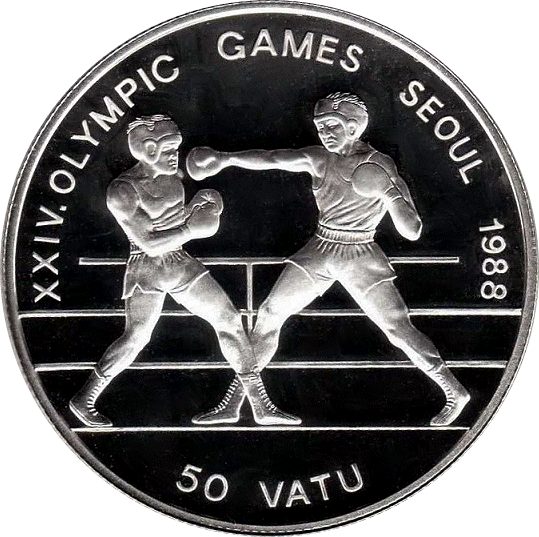

Here are a few 20th century coin designs by the Royal Mint whose designers I would like to know.

Maldives, 250 rufiyaa, 1992. Olympics.

Vanuatu, 50 vatu, 1988. Olympic boxers.

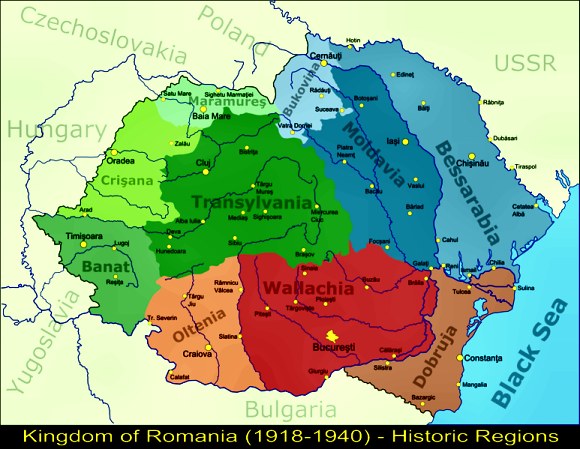

NOTE: On the map, “RUSSIA” would be better marked as “UKRAINE”. Part of Ukraine belonged to Russia and part to Austria-Hungary in those days.

After the devastation of the First World War, things could never be the same again, and empires fell. One of them was Austria-Hungary, which split into various parts. Today, in addition to Austria and Hungary, there are several countries whose territory lay wholly or partly within Austria-Hungary, including Ukraine, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro.

The ethnic Germans of Austria, who once ruled an empire, now inhabited a small impoverished country, which was both a republic and a democracy. Though politics in the new republic were fractious, many Austrians, whether socialist or conservative, wanted to join their ethnic brothers by merging with Germany. This hoped-for merger was known in German as the “Anschluss”. However, it was expressly forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles, though it continued to be an issue in Austrian politics.

Though the right-wing Christian Social party dominated Austria throughout the 1920, the working classes were now asserting themselves, and the Social Democratic Workers Party was the second largest grouping in parliament. Politics also continued in the streets throughout that turbulent decade, as socialists and right-wingers armed themselves with weapons left over from the war and formed private armies that fought occasional street battles. The situation mirrored that in Germany, where old soldiers formed Freikorps and battled with socialists and communists. In Austria the home-grown radical right-wingers formed themselves into local Heimwehren, each with its local leader. Nationally, they were known as the Heimwehr, but apart from being against socialists and communists and generally firmly right-wing, they had no specific coherent ideology.

Ignaz Seipel was chairman of the Christian Social Party from 1921 until 1930, and also Austria’s chancellor (the equivalent of prime minister in other countries) between 1922 and 1924, and again from 1926 until 1929.

In 1924 Seipel chose the cross potent, seen above, as the basis for the new national medal, the Austrian Order of Merit, presumably because it looked both military and Christian.

The Republic issued its first coinage in 1923 and 1924, denominated in Kronen (crowns), but because of inflation the currency was redenominated in 1925. 1 Schilling was now equivalent to 10,000 old Kronen, and new coins were issued that same year.

The 100 Kronen coin of 1923 and 1924 showed the head of an eagle. The head was crowned, despite the fact that Austria was a republic.

The 200 Kronen coin of 1924 depicted a cross potent, as used on the Order of Merit. The “S” in “OSTERREICH” is depicted in pseudo-runic form as a sigrune, which was allegedly a symbol of victory. This character became notorious in the 1930s, when, in its double form, it became the insignia of the Nazi SS. In the 1920s many Austrians and Germans were adherents of a romantic nationalism that was fascinated by such symbols, and this had been the case since the 1890s. For most, this was a harmless interest. I would compare such romantics to those Britons who are fascinated by the legend of King Arthur, some of whom are even convinced that he was a real person. Furthermore, artists and designers in the 1920s, after the war to end all wars, were also seeking new styles for new times. They were often keen to experiment with new uncluttered forms and brush away the old elaborate imperial devices.

The 1000 Kronen coin of 1924 depicts a Tyrolean woman in typical costume. Though it could appear that the design was a product of the ethnic nationalism of the time, in reality it is no more sinister than the Scottish pride in the kilt. It is more likely a political statement, since the South Tyrol, with its ethnic German-speaking Austrians, had been ceded to Italy after the First World War, and it is still part of Italy to this day.

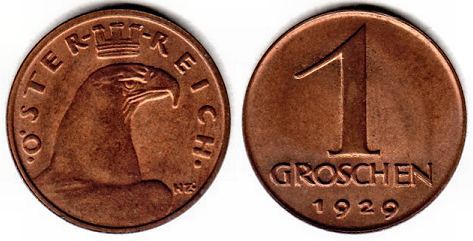

1 Groschen, 1929. A look at the redenominated coinage now. This coin was issued from 1925 to 1938.

2 Groschen, 1925. This coin was issued from 1925 to 1938.

The 5 Groschen was not added until 1931. It circulated until 1938. Note that the “S” in Groschen is in a ordinary font, unlike the pseudo-runic “S” in the country name.

The 10 Groschen was issued from 1925 until 1929.

The ½ Schilling was issued from 1924 to 1926.

The Schilling was issued from 1924 to 1926. It showed the Austrian parliament building.

Politics in Austria became more polarised as a result of the http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/July_Revolt_of_1927, when the Republican Protection League, the paramilitary street army of the Social Democrats, clashed with the police in Vienna. 84 protesters and 5 policemen were killed. The Heimwehr gained greater political prominence during the riot by intervening on the side of the police and in effect acting as the private army of the ruling Christian Social Party. Simultaneously, the Heimwehr was becoming more ideological due to its contacts with Italian fascists.

However, the Heimwehr, which believed that Austria should remain an independent nation, was unable to bridge its differences with the Austrian Nazis, who desired Anschluss. Its leader, Prince Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, therefore a founded a Heimwehr political wing in 1930, called the Heimatbloc (Homeland Bloc). As the Great Depression set in, more members of the Heimwehr and even the Christian Socials flocked to join the Austrian branch of the Nazi party.

Prince Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg.

Seipel had resigned as chancellor in May 1929, and in the parliamentary elections of November 1930 the Social Democrats gained more seats than the CSP, which retained power by entering a coalition with the smaller right-wing parties. The collapse of Austria’s largest bank, the Creditanstalt, in June 1931, intensified the Great Depression, and in Austria’s provincial elections of spring 1932 the Nazis gained 17% of the votes, becoming Austria’s third largest political party. Seipel died in August 1932 and in the following year he was commemorated on a special 2 schilling coin. Previously this annual commemorative had portrayed only musicians, but from now on it would be devoted to politicians.

Austria, 2 schilling, 1933: Seipel commemorative.

After a succession of short-stay CSP chancellors, on May 20 1932 Engelbert Dollfuss was sworn in as Chancellor of a precarious CSP-led coalition with a parliamentary majority of one. From farming stock, Dollfuss, only 4 foot 11 inches tall (150cm), had served with distinction in the First World War, afterwards rising through the Agriculture Ministry to become Minister of Agriculture and Forestry in 1931.

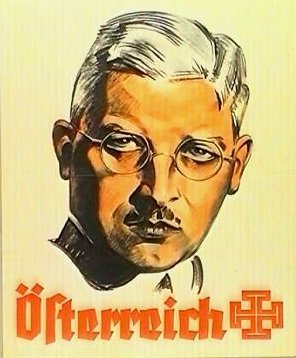

Engelbert Dollfuss, right.

Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in January 1933 and, with his aim of uniting all ethnic Germans, the threat he posed to Dollfuss was exacerbated by the existence of Austria’s own Nazis. Their credibility and electoral popularity was significantly enhanced by the emergence of the Third Reich, which also provided them with secret funds and support. Dollfuss was appalled by Hitler’s ruthless police state, which he regarded as no better than Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Surprisingly, from today’s perspective, the staunchly Catholic Dollfuss viewed fascist dictator Mussolini much more favourably. Mussolini, who had governed Italy since 1922, had concluded a concordat with the Vatican in 1929 and was seen by many at this stage as a moderate and effective leader. Mussolini was equally unimpressed by the newcomer Hitler and his ridiculous racial theories, and he supported an independent Austria as a buffer zone against Nazi Germany.

When, in secret talks, Dollfuss voiced his fear of Nazi subversion, Mussolini advised him to ditch democracy and adopt the fascist model. On March 4th 1933, during an intense parliamentary debate, the three presidents of Austria’s lower house stepped down in order to vote on measures against striking railway workers. This was strictly unconstitutional and left the house without a speaker. Seizing his chance, Dollfuss, supported by the president, declared the situation a crisis, locked the opposition out of parliament, and proceeded to rule by emergency decree, which he never lifted. At the end of March, Dollfuss banned the Republican Protection League, the paramilitary wing of the Social Democrats.

Dollfuss and Mussolini.

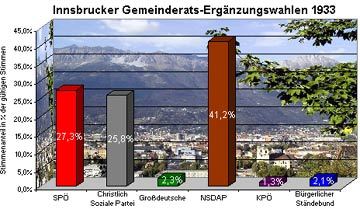

In April 1933 the Nazis emerged as the largest party in the Innsbruck city council elections, gaining 41% of the vote. It was Austria’s last democratic election before 1945.

Innsbruck city council election result.

On May 20th Dollfuss founded the Fatherland Front, which absorbed the governing parties of the former coalition, including the Heimatblock, and declared Austria a one party state. No longer “the Republic of Austria”, it was now the “autonomous, Christian, German, corporative Federal State of Austria”, a description that proclaimed its separateness from the unchristian Third Reich. Corporatism was borrowed from Fascist Italy: supposedly an economic middle way between socialism and capitalism, it was more theoretical than real.

Dollfuss banned the Austrian Communist Party on May 26th 1933. The Austrian Nazis, though still legal, resented their exclusion from the new state, and in solidarity Hitler imposed a 1000 Reichsmark fee on German tourists visiting Austria, crippling the country’s tourist industry. Throughout June Austrian Nazis indulged in terrorist acts, including bomb attacks on railways and arson. Inevitably, the Austrian Nazi Party was banned on June 19th.

Dollfuss in the uniform of the Heimwehr.

Dollfuss made a state visit to Rome in August, where Mussolini publicly promised to defend Austria’s independence by force of arms. Predictably, Dollfuss and his new regime were dubbed Austrofascist by his opponents.

Dollfuss in Rome.

The Fatherland Front adopted the fascist salute and the Nazi-like slogan “Front heil!”, while forming its own version of the Hitler Youth, the Austrian Jungvolk. The once innocent cross potent now stood service as the party symbol, looking suitably sinister as the counterpart to the Nazi swastika. Anyone visiting Austria and seeing the fierce eagle, the “Aryan” lady in costume, and the Nazi-like cross potent on the coinage might indeed have felt they were in an alternative Third Reich.

Dollfuss making a speech in September 1933.

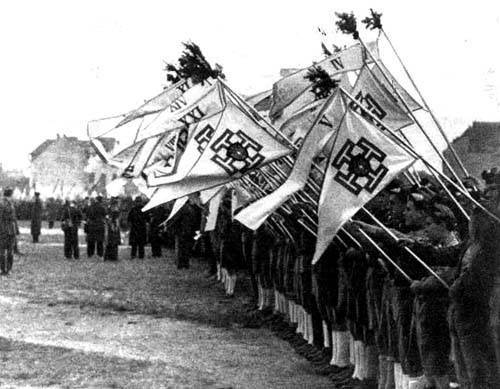

The Jungvolk.

Jungvolk members, with Dollfuss in the background.

In reality, though Dollfuss stole the fascists’ clothes, he despised the brutal, anti-semitic and atheistic Third Reich. Unlike Hitler, he sought, not a New Order, but a return to an older, more traditional one. Being devoutly Catholic, he reintroduced religious study to schools. Though he ran a harsh authoritarian dictatorship, he imprisoned and executed proportionately far fewer of his citizens than did Hitler. Modern political scientists label his regime not as fascist but as pseudo-fascist: reactionary and authoritarian but adopting a certain semi-fascist style. Salazar in Portugal and Metaxas in Greece headed similar pseudo-fascist regimes.

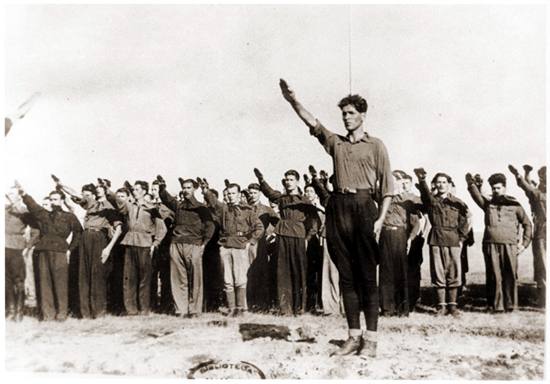

Fatherland Front rally.

Looking at the image of the rally above, I get the impression that the fascists and pseudo-fascists of the 1930s were influenced by the spectacle of “the movies”. “Talkies” had recently been developed, and Hollywood was becoming a powerful cultural influence. In his youth, Hitler himself had been impressed by the marches and demonstrations of the trade unionists and Social Democrats that he witnessed in Vienna. In that same city he also fell in love with Wagner’s operas. This synthesis of the power of politics and the spectacle of theatre/opera, produced on a mass scale, aided by the fast developing technology of the 1930s, made a great impression on the public of the day. The 1940s would reveal the scale of the brutality that lay behind the shallow fascist aesthetics.

Austria’s original coat of arms had been introduced in 1918 by the Social Democratic government. A single-headed eagle grasped a hammer and sickle, representing the industrial and agricultural workers, in its talons. The Federal State replaced this with a new coat of arms: the double-headed eagle, with haloes, harked back to the emblem of the Holy Roman Empire, and from 1934 to 1938 it appeared on the reverse of the coinage (50 Groschen and upward). The word “REPUBLIK” was also removed from the coinage. With the exception of the 50 Groschen of 1936, newly issued designs now employed the older spelling of “OESTERREICH”. The 1 Schilling coin was totally redesigned in 1934 and the depiction of the parliament building removed – appropriately, perhaps, for a dictatorship.

Austria, 1 Schilling, 1934.

50 Groschen, 1934.

On 12th February 1934, police searching for weapons in the Social Democratic headquarters of Linz triggered an armed conflict with the outlawed Republican Protection League. Violence spread to other parts of Austria but was mainly confined to working class districts of Vienna, where Dollfuss ordered light artillery to shell key apartment blocks. After several hundred deaths and numerous injuries, order was restored on 16th February, bringing an end to the so called Austrian civil war. Dollfuss promptly banned the Social Democrats and the trade union movement.

Austrian civil war.

On 25th July 1934, 154 Austrian Nazis disguised themselves as soldiers and policemen and broke into the chancellery building, shooting Dollfuss twice and leaving him to drown in his own blood. After their fellow conspirators broadcast on national radio that a regime change had taken place, Austrian Nazis rose up in various parts of the country. Fighting continued over several days, but it was eventually suppressed by the army.

Austrian Nazis preparing for the July Putsch.

The Austrian military and police deal with the siege.

The body of an Austrian sentry murdered by the Nazis is removed from a besieged building.

The Nazi putschists are captured and led away.

Dollfuss lies dead.

Mussolini had meanwhile rushed troops to the Austrian border in a clear warning to Hitler. Though the attempted coup had been well planned, Hitler predictably denied any involvement and thereafter reined in the activities of his Austrian Nazis. Kurt Schuschnigg, a quiet university professor, now took over as chancellor and the face of Austrofascism, and later in 1934 a special 2 schilling coin commemorated the death of Dollfuss.

Austria, 2 Schilling, 1934. Dollfuss commemorative.

Prince Starhemberg was reconfirmed as Vice Chancellor and made Federal Leader of the Fatherland Front. He had briefly been Acting Federal Chancellor after the death of Dollfuss, from July 26 to July 29, 1934.

A poster of Schuschnigg.

Schuschnigg, the new chancellor.

Starhemberg and Schuschnigg.

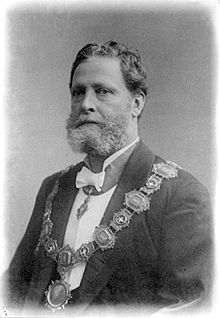

The annual 2 Schilling issue of 1935 commemorated the 25th anniversary of the death of Karl Lueger, the founder of the CSP and a mayor of Vienna. Credited with developing the modern Vienna, Lueger was known for his cynically anti-semitic propaganda – though in private he was not anti-semitic. As a young man in Vienna, Hitler himself had admired his rabble-rousing speeches, as he recounted in his autobiography, “Mein Kampf”. Did Lueger sow the seeds of anti-semitism in the man who would later instigate the horrors of the Holocaust?

Karl Lueger.

Austria, 2 Schilling, 1935. Karl Lueger commemorative.

A new 50 Groschen coin was issued in 1935 and also issued the following year, dated 1936.

Austria, 50 Groschen, 1935.

In November 1935 the League of Nations censured Mussolini when he invaded Ethiopia. In his isolation Mussolini cultivated Nazi Germany as an ally, and in November 1936 the Axis was born. Austria was now trapped between two large and aggressive powers.

Schuschnigg at a Fatherland Front rally in October 1937.

In February 1938 Hitler called Schuschnigg to a meeting in Berchtesgaden and ordered him to lift the ban on the Nazis and admit them into his cabinet or risk invasion. As gleeful Austrian Nazis ran riot, and amid mounting threats from Hitler, Schuschnigg in desperation arranged an independence referendum for 13th March, urging Austrians to vote against Anschluss.

With Mussolini’s tacit approval, a furious Hitler ordered his troops into Austria on 11th March. They encountered no resistance, only jubilation from cheering Austrians. Too many Austrians felt German, and too few felt loyalty to their young country, which had been subverted from within. The Anschluss was complete: Austria ceased to exist as a country and, with her currency now defunct, the German Reichsmark replaced the schilling.

A shattered Austria regained her independence after World War 2, and the single-headed eagle was reinstated on the country’s coins. Nobody now dreams of Anschluss, but in 2002 Austria and Germany both adopted the euro. With a shared currency once more, perhaps they could be said to enjoy “currency Anschluss”. It was also, of course, shared with the other members of the euro zone.

In essence, there was nothing wrong with the concept of “Anschluss”: merging with your ethnic kin in a single country. The Austrians suffered the grave misfortune of falling under Hitler’s rule, however. It was only one of many ironies that Hitler had been born an Austrian, though he later adopted German citizenship as an adult.

Dollfuss erected his own dictatorship because he had felt threatened by the Nazis. Emergency rule has often been used as a political method of avoiding a worse fate. Unfortunately for Dollfuss and Austria, fate was not on their side. Mussolini, once an opponent of Hitler, switched sides, while France and Britain looked the other way. Many Austrians were at first enthusiastic. After all, Austria was already a dictatorship, and Hitler had been born Austrian. Could things really get any worse? We all know the answer to that, but the Austrians were to find out the hard way.

For stamp collectors, here is an image of the Dollfuss memorial stamp issued in 1934.

During World War I Romania fought with France and Britain against Austria and Hungary. After the war, it was awarded parts of Hungary, Bulgaria and Ukraine, and the country more than doubled in size. However, Romania was still poor and very economically backward – 72% of the population worked in agriculture – and the country found it difficult to assimilate its new population. Many of its new citizens were Jewish, who accounted for 4.2% of Romania’s population. Anti-Semitism was quite commonplace and considered socially acceptable in the Romania of those times.

Politically Romania was dominated by the Liberal Party, which became increasingly conservative and nationalistic, and the right-wing National Peasant Party, which became increasingly authoritarian and nationalistic. There were no true centre parties, and only a small socialist and a tiny communist party. Elections in Romania were typically fraudulent and the results manipulated.

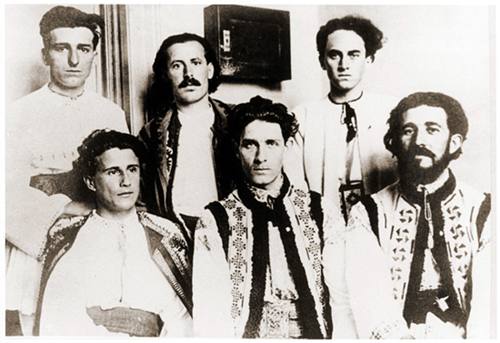

Codreanu and his bride at their wedding in 1925.

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu was born in 1899 in Huşi, which is now close to the border with Moldova. Too young to fight in the First World War, he moved to Iași in 1919 to study law. Though communism had very little presence or influence in Romania at that time, he maintained that he learned his anti-communism there while fighting communists on the street. Like the young Hitler, he despised the Soviet Union, which bordered Romania, and associated communism with the Jews. He had a deeply mystical sense of Romanians as a race, and, though he was also a fervent member of the Romanian Orthodox Church, his anti-semitism was racist above all. While in Iași, he fell under the influence of Professor Alexandru Cuza, who in 1923 founded the anti-Semitic National Christian Defence League, which used the swastika as its symbol. Later that year, Codreanu was charged with plotting to kill the Prime Minister and other government members, after they had passed laws giving equal rights to Jewish citizens, but he was acquitted because he had not set a date for the assassinations. Codreanu claimed to have had a vision of the Archangel Michael while in prison awaiting trial.

In 1924 Codreanu shot and killed a police prefect who had earlier beaten him while breaking up one of his political meetings. At his trial he was acquitted by jury members who were sympathetic to the League. In 1927 Codreanu urged Cuza to transform the League into a revolutionary paramilitary grouping, in effect a proto-fascist party, but Cuza was opposed to this. He then broke with Cuza to form the Legion of the Archangel Michael. Like other fascists, Codreanu favoured action over theory, claiming, “The country is dying for lack of men and not for lack of political programs.” He also professed his desire to create a “new man”. This was a standard aim among fascists, who considered their society and country to be decadent and degenerate and therefore in need of complete regeneration. This desire can also be seen in Hitler’s “New Order” and in the very name of the modern Greek Neo-Nazi party, “Golden Dawn”.

Codreanu and his thuggish comrades.

The Legionaries were fanatically religious. They believed that life consisted of violent struggle, both political and spiritual, and that there was nothing greater than to die for one’s country, race and faith. Their exaltation of self-sacrifice was tinged with religious fervour. The Legion introduced Orthodox rituals as part of its political rallies, while Codreanu made his public appearances dressed in folk costume. In common with the Nazis, he worshipped “Blood and soil” and held a romanticised view of the peasantry. Tall, handsome and charismatic, he would dazzle peasant audiences by riding into political meetings mounted on a white horse. But he was also a pathological anti-Semite. From Wikipedia:

Codreanu began openly calling for the destruction of Jews, and, as early as 1927, the new movement organized the sacking and burning of a synagogue in the city of Oradea. It thus profited from an exceptional popularity of antisemitism in Romanian society: according to one analysis, Romania was, with the exception of Poland, the most antisemitic country in Eastern Europe.

The Legion developed in a distinctly fascist direction, adopting the fascist salute and wearing paramilitary uniform, often with a swastika armband, and including a green shirt to symbolise the regeneration of Romania. Like the Nazis, the Legionaries were fanatically and violently anti-Semitic.

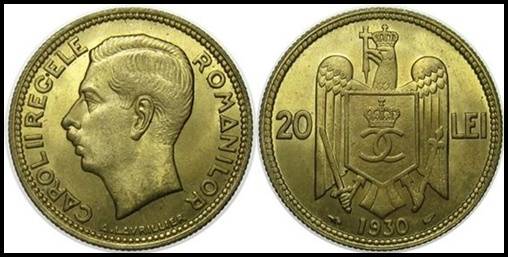

At the invitation of politicians who were dissatisfied with the regency, Prince Carol returned to the country on 7th June 1930 and was proclaimed king by parliament. The historian Stanley Payne describes King Carol II as the most cynical, corrupt and power-hungry monarch ever to disgrace a twentieth century European throne.

Carol II and his mistress, Elena Lupescu. Though Catholic, her parents had converted from Judaism to Christianity.

In 1930 the Legion created its own paramilitary arm, called the Iron Guard, just as Hitler had his Storm Troopers. Thereafter the Legion itself was often referred to as the Iron Guard. Codreanu also created Legionary death squads, numbering ten members or fewer. As part of their initiation rituals, they sucked blood from slashes that had been cut into the arms of other members. They then wrote oaths in their own blood, pledging to kill if ordered to. Squad members contributed their blood to a common glass, from which all drank, uniting them in life and death. (What is it with Romanians and blood? Count Dracula and Vlad Țepeș have a lot to answer for).

The government clamped down on the Legion from July 1930 onwards, after it had tried to provoke a wave of pogroms in Maramureş and Bessarabia. In one notable incident of 1930, Legionaries encouraged the peasant population of Borşa to attack the town’s 4,000 Jews. The Legion had also attempted to assassinate government officials and journalists — including Constantin Angelescu, undersecretary of Internal Affairs. Codreanu was briefly arrested together with the would-be assassin Gheorghe Beza: both were tried and acquitted. Nevertheless, the wave of violence and a planned march into Bessarabia caused the government to outlaw the party in January 1931; again arrested, Codreanu was acquitted in late February. To escape the ban, the party changed its name to the Codreanu Group and won 5 parliamentary seats in the general election of 1932.

In November 1933 King Carol II asked Ion Duca to head the government as prime minister in preparation for the December elections. Duca now moved against the Legion, which he considered to be dangerous and pro-Nazi, and also banned their political arm. Police on orders from Duca attacked and sometimes tortured Iron Guard members, which led to the deaths of some of them, and jailed around 1700 of them. On 30th December three Iron Guard members shot and killed Duca on the platform of Sinaia railway station in a revenge attack. All three of them were sentenced to jail for the murder. Because they were banned, the Legionaries had no political representation in the new parliament. The National Liberal Party won the elections and governed for the next four years.

In response to the ban on the Legionaries, in 1934 Codreanu formed a political party called “Everything for the Country” (“Totul Pentru Ţară”, sometimes translated in English as “All for the Fatherland”). The party was led by a general, but it was merely a front for the Legionaries.

In 1935 the National Agrarian Party and the National Christian Defence League merged to form the National Christian Party. The party was authoritarian, right-wing, and extremely anti-Semitic. It formed its own paramilitary group, known as the Lăncieri or Lance-bearers, who wore a blue-shirted uniform and a swastika armband. The Lăncieri and the Iron Guard were deadly opponents and often fought street battles, in addition to attacking Jews. Pity the poor Romanian Jews, who had to live in such an atmosphere.

Political scientists regard the National Christian Party not as fascist, but as pseudo-fascist. Apart from its anti-Semitism, it had no desire to reform the whole of society in a totalitarian fascist direction; it was in fact conservative in a reactionary and old-fashioned sense. It simply wanted people to know their place and stay out of politics if they did not agree with its message. True fascists, such as the Legionaries, were totalitarian, not merely authoritarian: they thought that if you were not with them, you were against them, so they required the whole population to engage in their activities and in the transformation of society and the state.

Also in 1935, Carol II formed his own paramilitary youth organisation, known as Straja Țării, The Sentinel of the Country, to counter the growing influence the Iron Guard had over the youth of Romania. Its members were known as străjeri (“sentinels”) and used the fascist salute as a greeting. The monarch modelled it on the Hitler Youth and the Italian Fascist Balilla. This became more obvious on December 3, 1938, when Straja Țării was re-organized along the lines of Carol’s personal regime replacing all existing youth movements, including Scouting, and became overseer of sports and all other activities. Its slogan was “Faith and work for country and king”. Credință și muncă pentru Țară și Rege.

The following year the Legion was involved in another atrocity. Mihai Stelescu, an ex-Legionary who had formed his own extremist group, was recovering in his hospital bed after an appendectomy, when a Legionary death squad, who considered him a traitor, burst in and shot him between 38 and about 200 times on July 16, 1936. They then cut him into pieces with axes and danced around his body. Arrested immediately, the men were sentenced to hard labour for life.

In the last months of 1937, by which time the Legion had around 200,000 members, Codreanu made several pro-German speeches. Romania’s expanded territory had been won at the expense of Germany’s former allies, making King Carol wary of Hitler’s growing power. Another general election was held in December 1937, and this time “Everything for the Country” made an electoral pact with the increasingly anti-Semitic National Peasants Party.

The National Liberal Party won 152 seats, with 36.5% of the vote; the National Peasants Party won 86 seats (20.7%); while Everything for the Country won 66 seats (15.8%). Together, the National Peasants and Everything for the Country pact had 152 seats, the same as the National Liberals, so there was a tie. As a result, King Carol chose Octavian Goga of the National Christian Party, which had received only 9.3% of the vote, to head a minority government. However, the chief of the police later admitted privately that “Everything for the Country” had actually won just over 25% of the vote in its own right, so in truth it was Romania’s most popular party. Evidently the King had arranged for the figures to be manipulated to show an apparent tie.

King Carol II in 1938.

In January 1938 the National Christian Party effectively stripped most Romanian Jews of their citizenship by setting an impossibly high bar for documentary proof of such citizenship. Jewish businesses were closed down; the resulting disruption took down many non-Jewish businesses and caused massive capital flight. The journalist Alexander Easterman wrote that “Goga proclaimed his policy, openly and unashamed, as designed to rid Romania of the Jews. Indeed, he had no other policy to offer; his government was quite simply anti-Semitic and nothing else”. Easterman hypothesises that Carol had placed this party in power “to give his people a taste of fascism”, hoping that a reaction against such policies would sweep away not only the relatively weak National Christians but also the far stronger Iron Guard.

The former rivals, Goga and Codreanu, now signed a pact on February 8th 1938. This alarmed King Carol, who initiated a royal coup d’état and deposed the Goga government on February 10th. He formed a new government, led by Miron Cristea, Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church. Romania was now governed by a royal dictatorship.

In March 1938, a government minister, Nicolae Iorga, accused Codreanu of serving Nazi interests and financing rebellion. Codreanu sent him an angry letter, accusing him of hypocrisy. Two weeks previously Hitler had annexed Austria, alarming King Carol and his government, who were now determined to crack down on Codreanu and his Legion. The Minister of the Interior, Armand Călinescu, therefore had Codreanu arrested for libelling a minister. The Minister of Defence, General Ion Antonescu, who later became dictator of Romania, gave evidence in Codreanu’s defence, but he was nevertheless sentenced to six months in prison. Antonescu resigned his government post in protest. Codreanu was then additionally accused of treason because of his Legionary activities and sentenced to 10 years’ hard labour, along with 44 of his top Legionaries. In November 1938 Carol visited Hitler, who offered his full support if Carol would get rid of his semi-Jewish mistress and release Codreanu from prison. Carol refused and returned to Romania.

On 24th November a Legionary death squad assassinated a relative of Călinescu. On 30th November it was announced that Codreanu and thirteen other Legionaries (members of his death squads) had been shot dead while trying to escape from prison. This incident became known in Romania as “The Night of the Vampires” – the Legionary death squads were notorious for their blood-drinking rituals. Much later the true story emerged: King Carol had ordered the Legionaries to be taken from prison and garrotted with wire. Meanwhile the remaining top Legionaries, including Horia Sima, their new leader, fled to Germany, where they began plotting revenge against the regime’s officials.

School notebook, 1938-1939. “Faith and work for country and king.”

In December 1938 King Carol created his own political party, the National Renaissance Front, which all members of the government were required to join. Jews were denied membership, but no new anti-Semitic laws were enacted. Romania was now a one party state. The government was organised on corporatist lines, imitating the structure of Mussolini’s regime. Party members wore special uniforms and ceremonial hats, and the fascist salute was mandatory. This was clearly an attempt to appease Hitler and Mussolini, but critics ridiculed it as “operetta fascism”.

On 3rd December 1938, Straja Țării was re-organised along the lines of Carol’s personal regime. It replaced all existing youth movements, including Scouting, and became overseer of sports and all other activities. Its slogan was “Faith and work for country and king”: Credință și muncă pentru Țară și Rege.

250 lei, 1939.

250 lei, 1939.

The edge inscription shows the motto of the King’s pseudo-fascist regime: MUNCA CREDINTA REGE NATIUNE (“Work, faith, king, nation”).

In March 1939 Călinescu became prime minister. On 21st September 1939, while being driven in his official car in Bucharest, he was ambushed and shot dead by Legionaries. They were caught, and a harsh repression of the Iron Guard followed, inaugurated by the execution of the assassins and the public display of their bodies at the murder site. Executions of known Iron Guard activists were ordered in various places in the country. Some were hanged on telegraph poles, while a group of Legionaries was shot in front of Ion Duca’s statue in Ploieşti. In all, 253 were killed without trial.

After Germany had completed its invasion of Poland in September 1939, Hitler continued to voice support for Hungary in relation to Romanian-ruled Transylvania. Romania eventually conceded to Germany’s economic demands, agreeing on March 7th 1940 to direct almost all cereal and oil exports towards Berlin. The country’s position became even more precarious after the fall of France in May 1940. As a direct consequence, Romania renounced its alliance with Britain and began attempts to join the Axis.

The National Renaissance Front was re-established as the Party of the Nation on June 21st 1940, being depicted as Romania’s “sole and totalitarian party” under the King’s leadership. Carol now appealed for Iron Guard assistance, even allowing its freed activists to join the Party of the Nation. On June 25th 1940 he signed an agreement with Horia Sima, who became Minister of Culture, and two other Guardists were appointed to similar positions. Sima resigned after only four days: his Legionary comrades objected to any association with Carol, who had previously persecuted them. The new authorities produced the first racial segregation laws, based on the Nuremberg Laws and aimed at Jews. These notably introduced the legal concept of “Romanians by blood”.

In the wake of the Nazi-Soviet Pact on June 26th 1940, the Soviet Union presented Romania with an ultimatum demanding the cession of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. As a result, Romania withdrew its administration from the region, leaving room for Soviet annexation. On August 30th 1940, Germany and Fascist Italy pressured Romania into signing the Second Vienna Award, which assigned Northern Transylvania to Hungary. Through the cession of Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria (by the Treaty of Craiova) in early September, Romania lost all its gains from World War I. As Hungarian troops entered Northern Transylvania, Bucharest became the scene of massive public protests, calling for the resignation of the government.

When General Antonescu protested against the losses, the King sent him to prison. However, he was also the most pro-Nazi man in the military hierarchy, and Hitler pressured Carol to have him released. Antonescu had promised the Nazis the mineral wealth of Romania for their war effort, if they would support him. Carol relented and asked him to form a military dictatorship and a cabinet. Antonescu accepted, then, with support from various political forces and the army, pressured Carol to abdicate. On September 6 1940 Carol left his throne and country, settling in Brazil at the start of 1941. Prince Michael, disgusted at Carol’s treatment of his mother, Princess Helen, refused to see him ever again.

Horia Sima, the new leader of the Legion of the Archangel Michael.

Prince Michael and King Carol II.

General Ion Antonescu, Conducător, and Deputy Premier, Horia Sima.

The 18-year-old prince now ascended the throne for the second time and issued a royal decree declaring Antonescu to be Conducător (leader) of the state. Antonescu lacked his own political base, and the establishment parties remained pro-British and pro-French, so he opted for a military dictatorship in coalition with the pro-Nazi Iron Guard, whom he regarded as the country’s political base. The Nazis approved of this, since they considered the Guard too weak to rule alone. The resulting regime, deemed the National Legionary State, was officially proclaimed on September 14th 1940. The Iron Guard was remodelled into a single official party: Antonescu continued as Premier and Conducător and was made Honorary Leader of the Legion, while Horia Sima was made Deputy Premier of Romania and Commander of the Legion.

In the first half of 1940, the 250 lei was again issued with the portrait of Carol II and the edge inscription “MUNCA CREDINTA REGE NATIUNE” (“Work, faith, king, nation”).

Michael, 250 lei, 1941.

In early 1941, the 250 lei was issued with the portrait of King Michael, but now the edge inscription read: “TOTUL PENTRU TARA”, meaning “Everything for the country”. This was the name of the Legion’s political party and also the slogan of the National Legionary State. The words on the edge inscription were separated by a small symbol, similar to a portcullis, that was the emblem of the Legion.

From romaniancoins.org

“The coins were released into circulation after March 19th, and withdrawn in May and June. It seems that about 94% of the coins that entered the market were withdrawn. Most probably the withdrawal was caused by the edge inscription. This issue was replaced by a new one, with NIHIL SINE DEO on the edge.”

250 lei, 1940, showing King Michael.

Here the date, 1940, is separated by the symbol of the Legion.

Additionally, some 250 coins of this type were produced with the date 1940 and the edge inscription “TOTUL PENTRU TARA”, but also bearing the symbol of the Legion, which separates the date. Most of these coins were melted down, but a rare few remain. You can read more about these coins here.

Romanian stamp, 7 lei, 1940. This stamp was issued on November 8th 1940 and commemorates the 13th anniversary of the founding of the Iron Guard by Codreanu, who was killed in 1938. The main symbol used by the Iron Guard was a triple cross, standing for prison bars and symbolising martyrdom.

Another stamp, issued by the Legion itself, showing the movement’s symbol.

General Antonescu and Horia Sima. Both are wearing a Legionary uniform.

In late September 1940, the new regime denounced all former pacts and diplomatic agreements, bringing the country into Germany’s orbit. German troops entered the country in stages, in order to defend the local oil industry and instruct the Romanians in Blitzkrieg tactics. In November Antonescu signed the Axis-sponsored Tripartite Pact and the Anti-Comintern Pact.

Antonescu did not oppose the Iron Guard’s policies, but he was offended by its paramilitarism and frequent recourse to street violence. There was tension between the leaders due to thieving by the Iron Guard from the Jewish population. Antonescu believed the robbery was done in a fashion detrimental to the Romanian economy, and that the stolen property did not benefit the government, only the Legionaries and their associates. He held that the expropriation should be done gradually through the passing of anti-Semitic laws.

The Legionary press began claiming that Antonescu was obstructing the revolution and aiming to take over the Iron Guard. In late November 1940, after uncovering the circumstances of Codreanu’s death, the Legionaries began violent retaliations against political figures. More than 60 former dignitaries or officials were executed in Jilava prison while awaiting trial, including former prime minister Nicolae Iorga, without even the pretense of an arrest. The Guard also pursued a campaign of anti-Semitic pogroms.

Angered by this insubordination, Antonescu ordered the Army to resume control of the streets. He ousted the Iron Guardist prefect of the Bucharest Police and ordered Legionary ministers to swear an oath to the Conducător. His condemnation of the killings was nevertheless limited and discreet, and he later joined Sima at a burial ceremony for Codreanu’s newly discovered remains. The dispute between the dictator and Sima’s party alarmed Hitler, who was preparing to attack the Soviet Union and feared that any internal conflict would threaten Romania’s vital oil industry.

Meanwhile the excesses and incompetence of the Legion were eroding its popularity with the public. The Legion’s “national socialism” subjected labour to hierarchical control and caused mounting economic disarray that provided no advantages to workers.

On 14th January 1941 Antonescu visited Germany to meet Hitler, who agreed to the elimination of his opponents in the Legionary Movement. Returning to Romania, on 19th January Antonescu issued an order cancelling the position of Romanian-isation Commissars: well-paying jobs, held by Legionaries. Additionally, he fired the Legionaries responsible for terror acts, from the Minister of the Interior to the commanders of the Security Police and the Bucharest Police. He appointed loyal military men in their place. The military also took control of strategic installations, such as telephone exchanges, police stations and hospitals. The district officers, who were Legionaries, were then called to the capital for a meeting, where they were arrested.

The issue was who would rule Romania, and Sima overplayed his hand. As their privileges were being cut off, the Legionaries erupted into an orgy of violence. The so called Legionaries’ rebellion, including the bestial violence of the Bucharest pogrom, occurred between 21st and 23rd January 1941. Armed Legionaries captured the Ministry of the Interior, police stations and other government and municipal buildings, and opened fire on soldiers trying to regain these buildings. The Legion organised mass drafts at neighbouring villages, and masses of peasants flooded the streets of Bucharest in response to the Legion’s call to defend Romania against the “Jews and Freemasons”.

In all, the Legionaries killed 30 soldiers and at least 125 Jews. On January 24th 1941, with Hitler’s approval and the support of the army and other political leaders, Antonescu moved in. The Guard attempted a last-ditch coup, but no fascist movement was ever a match for an organised army. In a three-day civil war, with support from the Romanian and German armies, Antonescu won decisively. The Legion was banned and 9,000 of its members were imprisoned. Antonescu then proclaimed Romania a “National and Social State,” with himself as sole dictator.

Hitler granted political asylum to Sima – whom Antonescu’s courts sentenced to death – and to other fleeing Legionaries. They were detained in special conditions at Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps. Antonescu’s government took anti-Semitism even further than the Iron Guard and became infamous for its participation in the Holocaust.

After the war, Sima fled to Spain, where he remained unpunished for his atrocities and died of old age in Madrid in 1993. In 1946 Antonescu was found guilty of treason by the Romanian communist government and executed by firing squad. In 1947 King Michael was forced to abdicate by the Romanian government. He settled first in Italy, then England, then finally in 1956 he made his home in Switzerland. He died there, aged 96, on 5 December 2017.

NOTE: After the demise of the Legion, new versions of the 250 lei coin were minted in 1941, with a portrait of King Michael and the edge inscription “NIHIL SINE DEO”, which was King Michael’s motto and is Latin for “Nothing without God”.

See also:

1] Iași pogrom.

2] King Michael’s Coup.

All fascist regimes are doomed to self-destruct, because they are so extremist that they believe in all or nothing, and they are so aggressive that they inevitably make too many enemies and are defeated. Mussolini’s regime took 22 years to self-destruct. Hitler managed it in only 12 years. The National Legionary State lasted from September 6th 1940 to January 23rd 1941, a mere 131 days. Ultimately they achieve nothing other than violence, murder, and mass agony. Sadly, the Legion was survived by Ion Antonescu, who was made a Marshal of Romania in 1942 and, though he was a military dictator and technically not a fascist, he was as brutal, barbaric and bestial as any fascist.

Sources:

1] Wikipedia

2] “A History of Fascism, 1914–1945”, by Stanley Payne.

Benito Mussolini was born in Predappio, northern Italy, in 1883. Growing up, he was strongly influenced by the socialist views of his blacksmith father. Though he was a bully at school and often badly behaved, Mussolini nevertheless qualified as a teacher in 1901. He moved to Switzerland in 1902, in order to avoid military service. There he became an active socialist and trade unionist, giving speeches and working for a socialist newspaper. In 1904 he returned to Italy to complete his military service. By 1911 he had become a leading socialist and editor of the Italian Socialist Party’s newspaper.

Young Mussolini.

When the First World War broke out in July 1914, Italy remained neutral. Mussolini at first opposed the war, along with his party, but as nationalism surged throughout Europe, he argued that Italy should join the Allies, since the war would trigger anti-imperialist revolutions and liberate those Italians still under Austro-Hungarian rule. The Socialists expelled him in October 1914 for his pro-war stance, but in November Mussolini, now funded by an armaments firm, started his own pro-war newspaper, called “The People of Italy”. In a speech given in December 1914, Mussolini maintained:

“The nation has not disappeared. We used to believe that the concept was totally without substance. Instead we see the nation arise as a palpitating reality before us! Class cannot destroy the nation. Class reveals itself as a collection of interests—but the nation is a history of sentiments, traditions, language, culture, and race. Class can become an integral part of the nation, but the one cannot eclipse the other.”

Though still a socialist, Mussolini was critical of dry theoretical Marxism, believing that the masses needed to be guided by a revolutionary elite and inspired by strong emotions and violent myths. Accordingly he founded the Fasci d’Azione Rivoluzionaria (Revolutionary Action Group) in December. A “fascio” (plural “fasci”), meaning literally “bundle”, was a loose political grouping. Many other pro-war “fasci” now sprang up.

Italy eventually joined the Allies in May 1915, tempted by promises of territorial gains. Mussolini entered military service in August 1915 but was invalided out with mortar injuries in February 1917. Italy initially suffered many military setbacks, but by early November 1918 it had occupied Austria-Hungary’s entire coastline, including Dalmatia. By the end of the war, however, Italy had lost 600,000 men and inflation was rampant. Italy gained the South Tyrol and part of Istria from Austria-Hungary, but the Allies gave Dalmatia, initially promised to Italy, to the new state of Yugoslavia, and furious Italian nationalists now denounced the “mutilated peace”.

In March 1919 Mussolini founded the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Combat Group) in Milan, with around 200 members of varying political views, but all of them extreme nationalists. Some were demobilised assault troops from the war. These battle-hardened young thugs continued to wear the black-shirted uniform and became known as “Blackshirts”, or alternatively “squadristi”, members of Mussolini’s action squads. However, Mussolini’s group gained only 0.5% of the vote in the November 1919 general election. The Socialists came first, followed by the Catholic People’s Party. Their mutual distrust prevented them forming a majority government, so the corrupt and oligarchic liberal elite continued to provide a weak minority government.

Fascist Blackshirts from a Fascio di Combattimento, 1920

In September 1919, with the help of 300 supporters, Gabriele D’Annunzio, a nationalist poet and war hero, occupied the city of Fiume (now Rijeka, in Croatia), which he believed to be Italian, proclaiming himself Duce of the Regency of Carnaro. He lamented that Italians, despite the unification of 1870, still did not think of themselves as a country. “We have made Italy, but we have not made Italians“. In Fiume he developed rituals, parades, ceremonies, uniforms and a style of salute that would eventually be copied by Mussolini. He also harangued audiences from a balcony and devised a constitution based on corporatism. On 12 November 1920 the League of Nations approved the Treaty of Rapallo, which overrode D’Annunzio and made Fiume a Free State. D’Annunzio refused to recognise this, then declared war on Italy. On 24 December 1920, the Italian government bombarded the port and forced D’Annunzio and his supporters to surrender the city. Mussolini had watched the affair with interest, while keeping his distance, though it proved to be a great influence on his political style. After D’Annunzio sank into oblivion, attention switched to Mussolini as Italy’s premier nationalist.

Meanwhile, through 1919 and 1920, the economic crisis in Italy caused soaring industrial and agricultural unrest. Strikes proliferated and, in August and September 1920, workers occupied factories and declared workers’ councils, while landless peasants seized plots of private land. Many feared there would be a Soviet-style revolution, but a weak government backed down and made concessions to peasants and workers. The unrest died down, but socialists still ran many municipalities, and frightened and vindictive landowners and industrialists now launched their fight-back. Increasingly they paid Mussolini’s squadristi to attack socialists and trade unionists and burn down their headquarters around the country. The anti-fascist Left was no match for the Blackshirts, who were better organised, better armed and far more brutal. Meanwhile, the police and military often cheerfully stood back or even supplied the Fascists with weapons, despite the government’s attempts to forbid this.

From “Mussolini the revolutionary”, by de Felice:

Between the end of 1920 and the first months of 1921, the Fasci completely changed physiognomy, character, social structure, key centres, ideology and even members. Of their leaders only Mussolini and a very few others completely followed this change in all its phases. Many original members fell by the wayside, and a number even passed over to the opposite side, but the majority almost inadvertently found themselves at a certain point different from what they had been in the beginning, supplanted in the leadership of the movement by new elements, of diverse origin and development, tied to quite different realities.

Fascism, finding the political space on the left already occupied, had now found a vacant space on the right. Fascist membership surged to almost 190,000 by May 1921, and the Fascists won 35 seats in that month’s general election. Mussolini, now a deputy, renamed his movement the National Fascist Party in November 1921. He shunned the three weak coalition governments that followed, denouncing socialism and liberalism alike. Going into 1922, in northern Italy the Fascists took over yet more regional councils by force, but still the state declined to intervene. Mussolini claimed that Fascist violence was a defence against the “red menace”, and he was eagerly believed by many. In October 1922, the impatient regional Fascist bosses urged Mussolini to launch a Fascist coup, but he would agree only to a Fascist “March on Rome”, to pressurise the government.

On October 27, Fascist squads took over strategic points across northern Italy and the march began. The military and police pledged their loyalty to the King, confident they could easily defeat the roughly 30,000 lightly armed Fascists. Next day the Italian premier advised the King to declare martial law. The King hesitated and so the premier resigned in protest. A nervous Mussolini had remained in Milan, but on the evening of October 29, the King asked him by telephone to join a new government. Emboldened, Mussolini insisted on becoming Prime Minister. The King agreed. He wanted an end to weak government and to avoid a potential civil war by co-opting and taming the Fascists, who already had much support within the establishment. On October 30, Mussolini travelled to Rome by train to become premier. His marching Fascists arrived the next day, and Mussolini briefly joined them to pose for photographs. He now fronted a coalition government, but the establishment had unwittingly invited a cuckoo into the nest.

The March on Rome: Mussolini and his Fascists, October 1922.

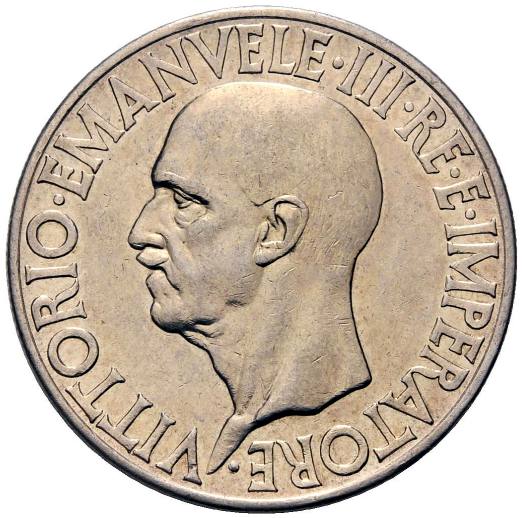

Gold 20 lire and 100 lire coins were issued in 1923 to commemorate the anniversary of the March on Rome. The coins show King Vittorio Emanuele III on the obverse and the fasces on the reverse. The Fascists had adopted the Roman fasces as their party symbol. The fasces, a bound bundle of rods enclosing an axe, was an ancient Roman symbol of state authority, which the Fascists had adopted as their party emblem. The Fascists had blasted out an ideological space for themselves by claiming to be heirs to the ancient Roman spirit, with which they would forge a modern Roman empire. The bound rods symbolised strength through unity, reflecting the collectivist ethos of the Fascist mass movement. The fasces represented discipline and potential punishment, again reflected in the Fascist slogan of “Order, discipline, hierarchy”. The Fascists despised what they saw as the sordid compromises of democracy and its insipid egalitarianism, lauding instead strong leadership and heroic acts and maintaining they had seized power through their March on Rome. In fact, the marching Fascists had arrived in Rome only after a power-sharing deal was made. In Munich, an admiring Hitler believed the myth and attempted his own coup in October 1923, but he learned a harsh lesson when it was swiftly put down.

Italy, gold 20 lire, 1923.

Italy, 100 lire (gold), 1923.

A nickel 2 lire non-commemorative circulation coin, with a similar reverse design to the 20 lire coin, was also issued from 1923 to 1927. The 2 lire reverse was designed by Publio Morbiducci but engraved by Attilio Motti. Morbiducci later produced some superb patterns in the competition for the Irish Free State’s first coinage. The 20 lire reverse was designed and engraved by Motti. Curiously, he replaced the usual lion’s head, above the axe blade, with a ram’s head.

Italy, 2 lire, 1923.

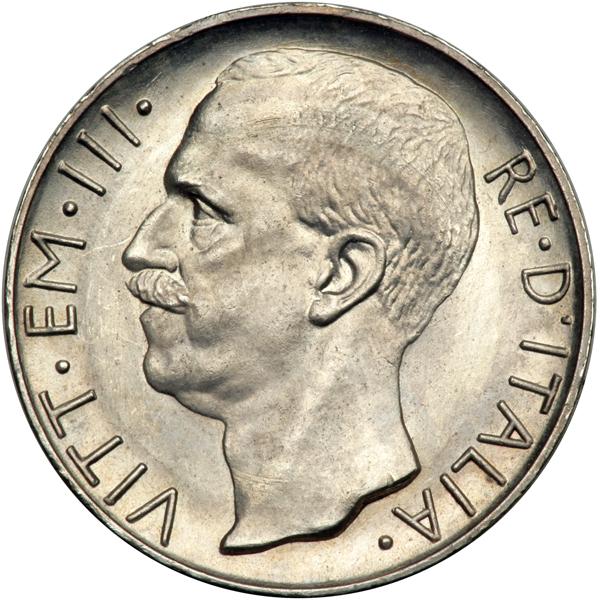

Over the next two decades, the fasces would become as ubiquitous in Italy as the hammer and sickle in the Soviet Union. Fascism, the bastard child of socialism, came to be seen as the mirror opposite of communism, and both were collectivist mass movements that aspired to a one-party totalitarian state. However, the royal portrait on these coins emphasises one major difference: whereas communists came to power by force and smashed the existing system, the Fascists were helped into power by the existing elites. Fascist Italy was in fact a diarchy, in which the King remained head of state, while Mussolini was head of government. Though Mussolini styled himself “Il Duce” (“The Leader”), his portrait never appeared on the coinage; by tradition, that privilege was reserved for the head of state, namely the King. But the monarchy and Fascism were now locked in an embrace that would end in their mutual destruction.

The fasces had appeared on many coins worldwide before the Fascist regime adopted it, most notably on the US dime, from 1916 to 1945.

US Mercury dime with fasces, 1936.

Mussolini initially ruled by emergency decree for one year, introducing business-friendly laws, but now in July 1923 he proposed an election law that would give two-thirds of parliamentary seats to the party with the most votes, provided it gained at least 25% of the votes. Many deputies abstained but, with armed Fascist guards at the doors, the remainder was intimidated into voting for the law. The general election was held in April 1924, amid much intimidation, and the Fascist Party duly gained 65% of the vote, so the new law made little difference. When parliament convened on May 30, socialist deputy Matteotti denounced the Fascists’ violence and electoral fraud. On June 10 he disappeared, and his body was found on August 16. He had been murdered by Fascist thugs, who were duly imprisoned. Mussolini denied involvement but remained paralysed with indecision as the scandal dragged on. On December 31, thirty leading Fascists told him to declare a dictatorship or else they would depose him. On January 3 1925, a combative Mussolini told parliament that he accepted responsibility for Fascist errors. However, he would not resign but would continue to govern Italy – “by force, if necessary.” In a still polarised country, he retained the confidence of the King and the establishment. He now purged his violent squadristi but also took control of the Press and banned trade unions (apart from Fascist ones) and strikes. After a failed assassination attempt against him in 1926, he banned all opposition parties, and in 1927 he created a state secret police force. For Mussolini, the state was paramount: “Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.” In 1928 he replaced parliament with the Chamber of Fasci and Corporations. His rule was now complete, and he was answerable only to the king.

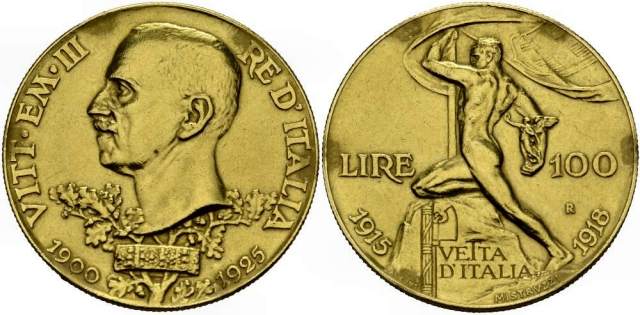

After the commencement of Mussolini’s dictatorship, Italy predictably issued more coins with Fascist-inspired designs. A gold 100 lire coin of 1925 jointly commemorated the King’s silver jubilee and the tenth anniversary of Italy’s entry into the World War. The reverse includes the fasces and shows a nude male holding a statue of the goddess of Victory, while kneeling on “The Peak of Italy” (Vetta d’Italia) and planting an Italian flag on it. This mountain stands in former Austrian territory that was ceded to post-war Italy. Until now, nudes on Italian coins had been female, but Fascism was a fundamentally masculine creed. The muscle-bound male projects the youth, virility and heroism to which Fascists aspired. That this distinctly propagandistic piece commemorates World War I is particularly apt, since Fascism derived all its values from that war: murderous nationalism, state-directed violence, and the militaristic values of discipline, hierarchy and camaraderie.

Italy, 100 lire (gold), 1925.

A new silver 10 lire was issued in 1926. Its reverse shows an allegorical female driving a chariot. Only the fasces held by the woman identifies this as a Fascist issue.

Italy, 10 lire, 1926.

A new silver circulation 5 lire was issued in 1926, through to 1935. The reverse depicted an eagle, perching on the fasces. Such fierce eagles were portrayed on the military standards of ancient Rome, whose martial qualities Fascism aspired to emulate. Fascist propaganda made constant allusions to ancient Rome.

Italy, 5 lire, 1926.

Unadopted trial design of the 5 lire.

Compare the 5 lire to the Albanian 2 franga ari of 1926, also a product of the Rome Mint.

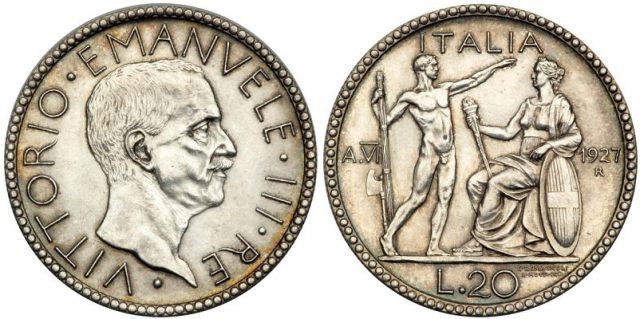

Yet like the Jacobins of the French Revolution, the Fascists also claimed to have inaugurated a new era, which required its own calendar: Year 1 of the Fascist Era accordingly began with the march on Rome in 1922. A new silver 20 lire, issued in 1927, was the first coin to give the year in both the Christian era and the so called Fascist era. However, the commonly issued version of this coin shows the letters “A.VI” next to the fasces, an abbreviation of “Anno VI”. Only 100 pieces were minted with the correct Fascist Year 5, “A.V”. A 1928 version of the coin was issued with the Fascist year correctly shown as “A.VI”. The Roman numerals overtly allude to the Fascists’ identification with ancient Rome. The reverse design shows a standing nude male holding the fasces before a seated Italia, perhaps symbolising Fascism protecting Mother Italy.

Italy, 20 lire, 1927.

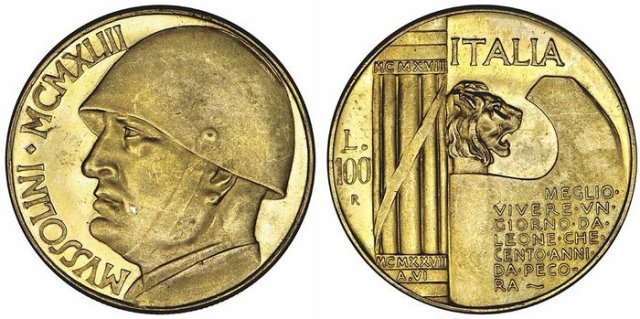

Also in 1928, a blatantly triumphalist 20 lire silver coin was issued to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the World War. The reverse design showed a fasces, on whose axe blade was written the boastful motto: “Better to live one day as a lion than a hundred years as a sheep”. The obverse design continued the war-like theme by portraying the King in a military helmet.

Italy, 20 lire, 1928.

By 1928, Mussolini, aided by his skilful propaganda, was admired by many in the West as a moderate and effective dictator, who provided strong government after Italy’s years of strife. In 1870 the Kingdom of Italy had annexed the last of the Papal States, earning the enmity of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1929 Mussolini negotiated the Lateran Pacts with the Holy See, whereby the Vatican City was given its own small sovereign state and financial compensation for its territorial losses. Mussolini, the former socialist, atheist and anti-clerical republican, had now made his peace with both the Pope and the King – to the disgust of many early Fascists, who had long since left the Party. This acted as a restraint on his regime, which, though repressive, was far less brutal than some of its contemporaries.

Mussolini and the King.

Fascism claimed to transcend class conflict, and this sense of idealism appealed to many Italians. Its emphasis on action particularly appealed to young people and students. Its reverence of the state appealed to people who worked in the public sector, but generally not to front line workers in private industries, such as miners and factory workers. In practice, the banning of strikes and the state’s need to favour productivity over consumerism meant that the Fascist regime was right-wing. It took care, however, to give some sops to workers, and its Dopolavoro (“After work” organisation) provided the public with various free and subsidised leisure activities, so that Fascism seemed to penetrate much of public and private life. But by now, most Fascist party members were mere opportunists, since membership could help advance their career.

Fascist Italy issued a gold 50 lire collector coin in 1931, whose legend, as was now standard practice, references both the Christian and Fascist era years: “1931-IX”. The reverse design shows a Roman lictor with fasces. A lictor was a Roman civil servant who acted as a bodyguard to magistrates.

Italy, 50 lire (gold), 1931.

A companion gold 100 lire coin was also issued. Its reverse design features the fasces superimposed on the prow of a galley, on which an allegorical Italia is standing. The legend “IX.E.F” refers to Year 9 of the Fascist era (“Era Fascista”). The 50 and 100 lire coins were also issued in 1932 and 1933, bearing the appropriate dates.

Italy, 100 lire (gold), 1931.

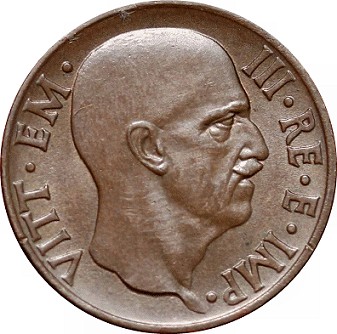

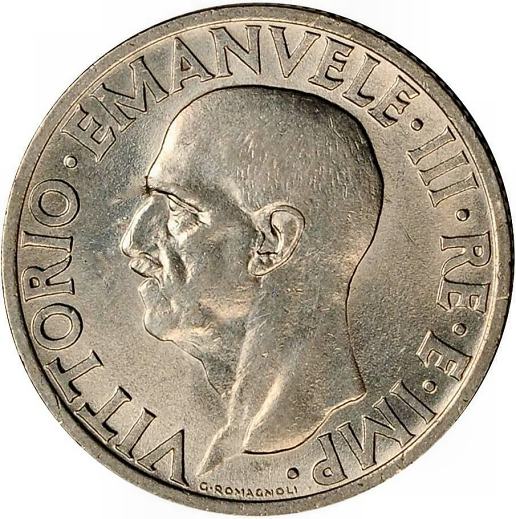

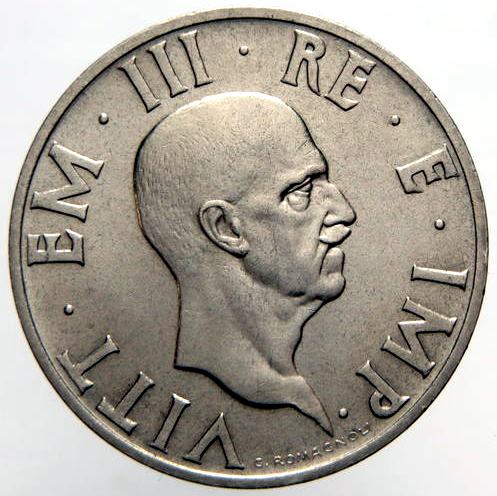

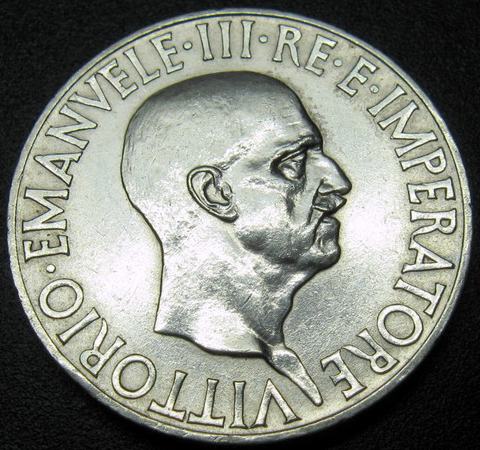

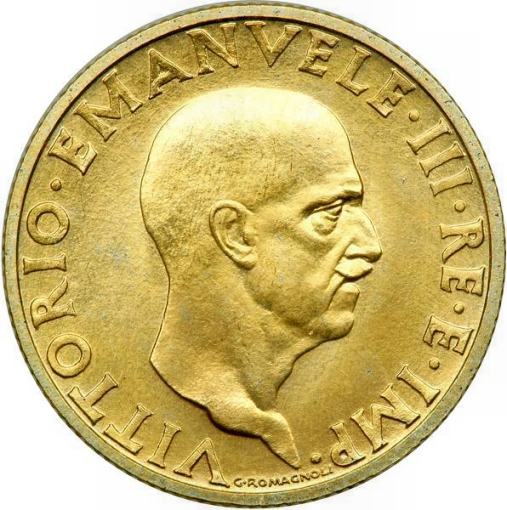

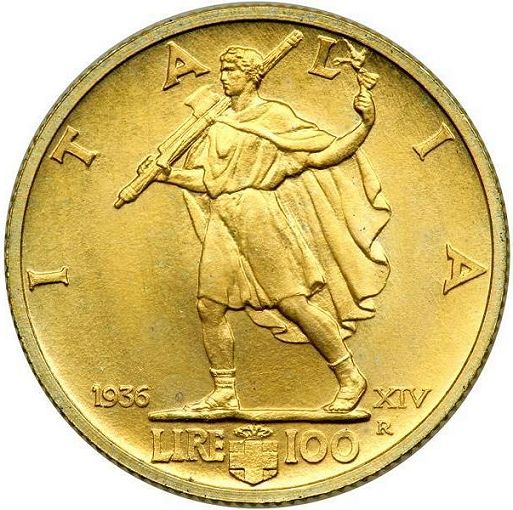

After the Great Depression hit, extremist politics became vogue and Fascism was much imitated across Europe by new extremist parties. Hitler came to power in 1933 as an avowed admirer of Mussolini, but the Duce, who had a Jewish mistress at that time, was unimpressed by Hitler’s bizarre racist theories. When Austrian Nazis murdered Austrian chancellor Dollfuss in a failed coup attempt in July 1934, Mussolini rushed troops to the Austrian border to warn Hitler off. Yet Mussolini harboured his own ambitions and now that he had consolidated his rule, he was looking for opportunities for glory. At home, he was increasingly stung by criticisms that he was presiding over a stagnant regime that lacked direction. In 1935 Mussolini decided to invade Ethiopia, Africa’s only remaining independent state, as a response to its border skirmishes with Italian Somaliland. After its conquest in 1936, Mussolini merged it, with Italian Eritrea and Somaliland, into Italian East Africa, and King Vittorio Emanuele was made Emperor of Ethiopia. Mussolini’s popularity in Italy was now at its height. In that same year, a new design series was released to celebrate the newly extended Italian Empire. The obverse legends now incorporated a reference to the King’s new status of Emperor. The Italian coinage was now become fully Fascist. Four different designs of an eagle perched on the fasces appeared on the 5 and 50 centesimi coins and on the 1 lira and 2 lire coins. These superb eagle designs echoed a similar 5 lire design of 1926. All the reverse designs showed the fasces and the crowned shield of the House of Savoy.

Italy, 5 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 5 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 20 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 50 centesimi, 1936.

Italy, 1 lira, 1936.

Obverse of the 1 lira coin.

Italy, 2 lire, 1936.

Obverse of the 2 lire coin.

The silver 5 lire coin depicts a mother with four children, representing “fertility”. Mussolini had instigated his pro-natalist “Battle for Births” policy in 1927, aiming to increase Italy’s population from 40 to 60 million by exempting families with ten or more children from income tax. He believed that a “great power” such as Italy required a large population, with which to wage war and conquer new territory. For that, he needed Italy’s mothers to provide him with lots of Fascist babies, who he hoped would grow up to join Italy’s conquering armies. The propagandistic “fertility” design was therefore an invocation to Italy’s women to remember their duty.

Obverse of the 5 lire coin, 1936.

Italy, 5 lire, 1936.

Mussolini inspects the Fascist baby production line.

The designs of the circulation silver 10 lire coin and the gold 50 lire collector coin echoed the designs of the 50 and 100 lire gold set of 1931, while the design of the silver 20 lire (a woman driving a quadriga) was reminiscent of Italian designs of the First World War. The gold 50 lire coin, however, carried a design that cleverly incorporated the fasces and the royal shield as parts of an ancient Roman standard, topped by the traditional eagle. The obverse designs portrayed the King as usual, but the legends now celebrated his new imperial status (“IMP”, “IMPERATOR”).

Obverse of the 10 lire coin.

Italy, 10 lire, 1936.

Obverse of the 20 lire coin.

Italy, 20 lire, 1936.

Obverse of the gold 50 lire coin.

Italy, 50 lire (gold), 1936.

Obverse of the gold 100 lire coin.

Italy, 100 lire, 1936.

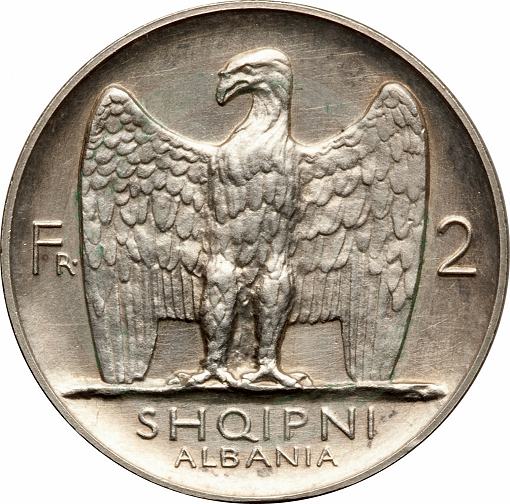

In November 1935 the League of Nations had censured Mussolini for his invasion of independent Ethiopia. In his isolation Mussolini now cultivated Nazi Germany as an ally, and when the Spanish civil war broke out in 1936, the two dictators provided military aid to General Franco and his nationalists. The Fascist slogan, “Believe, obey, fight!” reflected the Duce’s old-fashioned view that war kept a nation fit. Mussolini did not object when Hitler annexed Austria in 1938 and then dismembered Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939. Mussolini nevertheless regarded Hitler with fear and envy, and in 1938 he cynically introduced his own anti-Jewish laws to appease the Führer. Fortunately, most Italians ignored them. Many now felt Mussolini was “licking Hitler’s boots”; nor did they welcome war in Europe, and Mussolini’s popularity plummeted. But because he believed Italy’s destiny was to dominate the Mediterranean, and to compete with Hitler, the Duce ordered the invasion and conquest of Albania, which was completed in five days, from April 7 to April 12, 1939. Vittorio Emanuele now became King of the Albanians, and, between 1939 and 1941, coins were minted for Albania that showed his portrait on the obverse, while the reverse of the higher denominations depicted the Albanian eagle between two fasces, with the year shown in its Christian and Fascist era versions. On the 0.20, 0.50, 1 and 2 lek coins, the King wears a military helmet, which must have been deeply humiliating to the Albanians who used them.

After Germany invaded France in May 1940, Mussolini, expecting a swift German victory, cynically declared war on France and Britain on 10 June 1940. His troops invaded France ten days later. After its defeat, France signed an armistice with Germany on June 22. A Franco-Italian armistice was signed on June 24. Italy then annexed part of Menton, in South East France, and also established a small occupation zone that included Nice and Grenoble.

Italy, 5 lire, 1940 – trial.

In October 1940 Mussolini invaded Greece, but by November the brave Greeks had the Italians on the back foot. Hitler intervened with a blitzkrieg occupation of Greece and also Yugoslavia, but to do so he had to postpone his planned invasion of Russia. Mussolini gained Dalmatia, most of Slovenia, and established a protectorate over Montenegro, but Italy did not issue any special coinage for these new conquests and annexations.

Germany: “Two peoples and one struggle”.

Libyan stamps, 1941: “Two peoples, one war”.

Italy, 1941: “Two peoples, one war”.

Originally Mussolini had reckoned on a short European war, not a protracted world war. Financially, his military exploits to date had proved extremely costly, since Italian industrial output could not match that of Britain or Germany, meaning that Italy’s military was grossly under-equipped. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, both Mussolini and Hitler declared war on the USA. One year later, the USA dropped the use of the Bellamy salute, which had originated in 1892 as part of the Pledge of Allegiance, because it resembled the Fascist and Nazi salutes.

Disaster beckoned as the British gradually trounced Italy’s forces in North Africa, and by 1943 industrial unrest swept across Northern Italy itself. Italians had lost faith in Mussolini and no longer wanted to fight Germany’s war. Anglo-American forces took Sicily on July 9 1943, and at a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 24 July 1943, dissident Fascists voted for the King to reassume his governmental powers. An apathetic Mussolini ignored the vote, but when he visited the King next day, the King dismissed him as prime minister and placed him under military arrest.

The military flag of the Italian Social Republic featured a Roman eagle clutching the fasces.

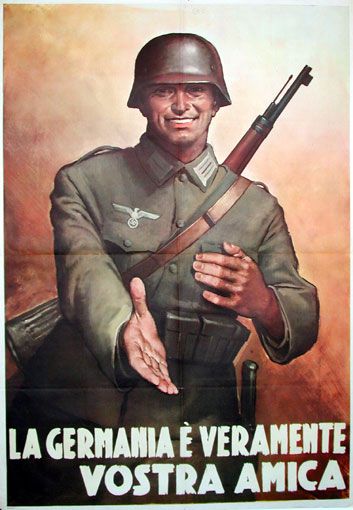

On September 8, as the Allies were liberating southern Italy, the Germans occupied northern and central Italy, rescuing a reluctant Mussolini and installing him as dictator of the short-lived Italian Social Republic. The rump regime issued a few stamps and banknotes but no coins.

Unsubtle propaganda in the Italian Social Republic: “Germany is truly your friend”.

In reality, Mussolini was now the mere figurehead of a German puppet state, where the brutal German military administration, aided by die-hard Fascist collaborators, made all the important decisions. Its nominal capital was still Rome, but its de facto capital was the small town of Salò. According to Stanley Payne, a historian of fascism: “The experience of the Salò regime discredited Mussolini more than the twenty years of Fascist government which preceded it.”

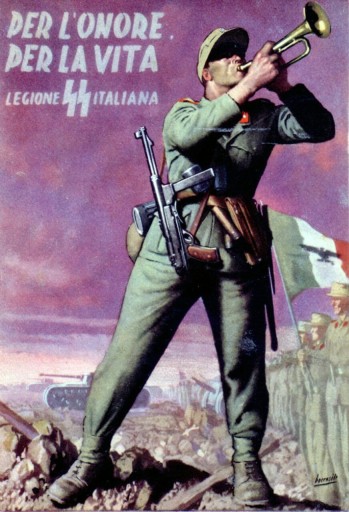

Around 15000 Italians fought in the Italian Waffen-SS Legion. The Nazis recruited many foreign nationals into the Waffen-SS.

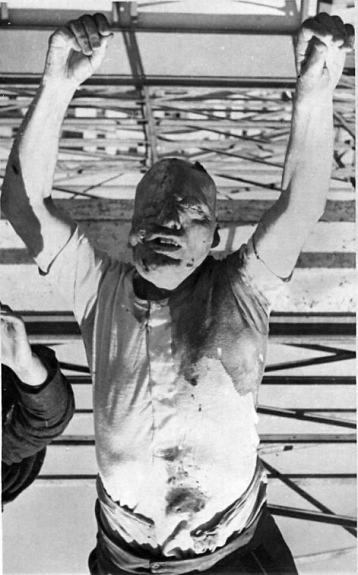

Meanwhile the King fled to southern Italy with his military government, where he arranged an armistice with the Allies. On October 13 1943 his government declared war on Germany, and the two Italian regimes descended into the chaos of civil war: Allies and partisans versus Nazis and Fascists. In April 1944, the King transferred most of his royal powers to his son, Umberto. On 27 April 1945, partisans captured Mussolini and his mistress en route to Switzerland, as they tried to escape. Both were executed by shooting the next day. Their bodies were taken to Milan, where they were hung upside down outside a petrol station and mutilated by an angry mob. Meanwhile, in Berlin, Hitler blamed his own downfall on his “fatal friendship” with Mussolini, before committing suicide on April 30. Though Mussolini’s dictatorship had been mild compared to Hitler’s, his regime’s naked aggression abroad meant that it reaped a rich harvest of retribution, and he deserved his ignominious fate.

Mussolini’s body hangs upside down in Milan.

From Wikipedia:

Initially, Mussolini was buried in an unmarked grave but, in 1946, his body was dug up and stolen by fascist supporters. Four months later it was recovered by the authorities who then kept it hidden for the next eleven years. Eventually, in 1957, his remains were allowed to be interred in the Mussolini family crypt in his home town of Predappio. His tomb has become a place of pilgrimage for neo-fascists, and the anniversary of his death is marked by neo-fascist rallies.

Mussolini brought death and destruction to his country. It is quite remarkable that anybody should want to honour such a failure.

The King abdicated in May 1946 and was briefly succeeded by his son, Umberto III. In a referendum the following month, 52% of the electorate voted to abolish the monarchy, which had been fatally tainted by its close association with Fascism. The ex-King retired to Egypt, where he died in 1947. Umberto moved to Portugal and died in 1983.

In 1999 and 2000, Italy issued a series of collector coins entitled “Goodbye to the lira”. It reproduced lira designs from the first half of the twentieth century. Astonishingly, one of them was the distinctly Fascist lira design of 1936.

Italy, 1 lire, 2000.

Just imagine if the Germans had reproduced a design depicting the Nazi swastika.

After the war, various fantasies portraying Mussolini were produced in Italy in the 1970s, by and for neo-fascists. Their reverse designs are clearly based on those of actual Italian coins of the 1920s. Because of this, some collectors believe that these fantasies must be trials, patterns or even fantasies produced during the Italian Social Republic, or during the prior Fascist regime of the Kingdom of Italy. This is emphatically not the case. No such patterns or trials were produced by either of the Fascist regimes, nor were any such unofficial fantasies produced during those periods.

Mussolini fantasy of the 1970s.

Mussolini fantasy of the 1970s.

After World War 2, a fantasy set of supposedly unissued stamps for Alpenvorland-Adria appeared on the market. It was alleged that they were produced in the final days of the war. In 1943 the German military had occupied the South Tyrol, which was part of the territory of the Italian Social Republic, with the intent of re-merging it into Austria. Austria was of course part of Germany at that time, having been annexed in 1938. See: Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills. The Italy had itself originally annexed the South Tyrol, which still was home to many ethnic German-speaking Austrians, as a result of the post-First World War territorial treaties. Though these alleged stamps were produced to a high standard and look similar to, though different from, the war-time set for “Provinz Laibach” (German-occupied Slovenia), it is clear, for various reasons (including the type of paper used), that they could not have been produced before the 1960s. They are therefore, however fascinating, mere fantasies (or “cinderella stamps”).

This gallery contains 2 photos.

Note how similar the Tuvalu 1976 5 dollar coin looks to the Kiribati dollar of 1976 below – which is documented as Michael Hibbit’s design. Here again, the style on the Tuvalu $10 of 1979 looks very similar. I’m pretty … Continue reading

Now that we are in 2013, the numismatic trends of the 21st century are becoming easier to discern. Some of them originated in the last part of the 20th century but have since become more widespread and visible. In every case, there are also examples that go against the trend, but by definition they are fewer than those following the trend.

I want to confine myself here to those trends that affect circulation coins. No doubt there are trends involving collector coins, proof and mint sets, marketing gimmicks, etc., but these are of no interest to me.

The disappearing humans

The first trend I have noticed is that there are fewer humans on coins: not generic humans, such as those depicted riding a horse, or driving a tractor, or whatever, but known personalities. A good example is Latin America, where, back in the late 20th century, the circulation coins of almost every country used to include portraits of their national heroes and liberators of the 1800s – generally high-collared military men with side whiskers.

The liberation of Latin America from its mainly Spanish rulers took place roughly between 1810 and 1830. It was occasioned by Napoleon’s invasion and conquest of Spain and Portugal. He made his own brother king of Spain, whilst the whole Portuguese royal family promptly sailed to Brazil and set up court there. There are still plenty of Latin American countries that honour their national heroes on their coins, but we have seen both Uruguay and Colombia adopt thematic wildlife designs in recent years – 2011 and 2012 respectively. We must assume that, as time has passed, these countries are feeling more secure in their nationhood and no longer feel the need to hark back to their old heroes. However, outside Latin America, the most noticeable country bucking this trend is Jamaica, which used mainly wildlife designs in the 1970s but has switched to national heroes since the 1990s.

Uruguay, 1 and 2 pesos, 2011.